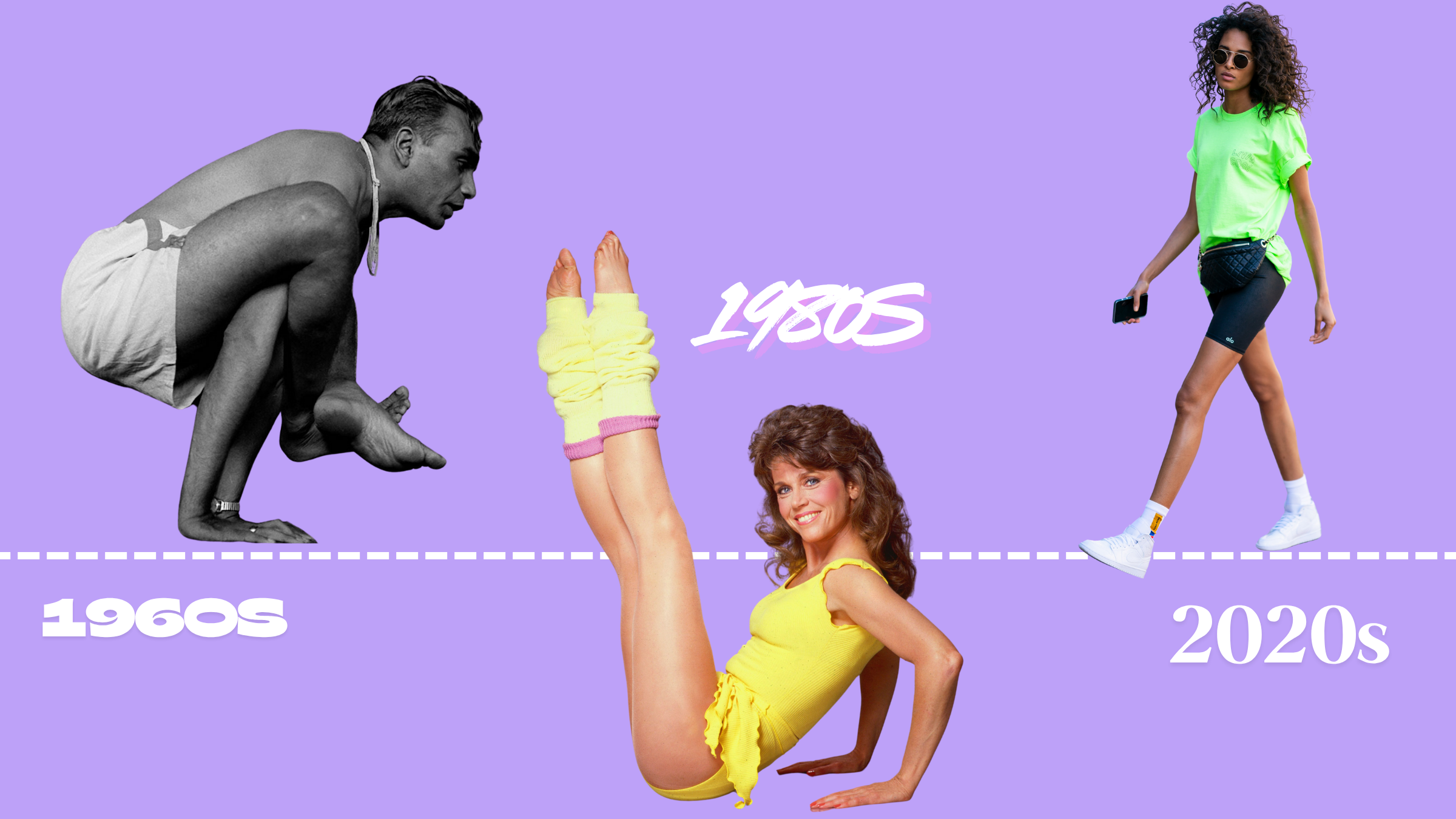

Throughout America’s obsession with yoga the last half century, our perception and interpretation of it has changed considerably with each decade. The 1990s saw yoga transition from an increasingly popular part of the country’s fitness craze to yoga being everywhere, endorsed by celebrities, and forever changing fashion with the introduction of leggings. As what was once considered woo-woo shifted to the latest workout craze, our culture’s limited absorption of the ancient tradition veered into appropriation. The following article explains all that and more as part of Yoga Journal’s 50th anniversary coverage of yoga’s evolving role in America throughout the 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, 2010s, and 2020s.

As a teenager walking around New York City in platforms and baby tees during the 1990s, I didn’t know anyone who practiced yoga. Sure, I had experimented with a Rodney Yee VHS tape, attempting my first Tree Pose in my living room as he balanced stoically on a mountain, but yoga mostly felt distant and mysterious. I was familiar with meditation, spiritually inclined, and vaguely knowledgeable about Eastern philosophy from books I’d read, but the dots weren’t connecting. I was just a girl roaming the East Village trying to find herself.

Ultimately, yoga found me—and millions of other Americans—during this decade. Previously associated with pretzel poses, ashrams, and esoteric spirituality, yoga began to show up on gym class schedules alongside dance and boxing and became increasingly linked with secular inner exploration. The 1990s introduced a broader audience to the practice, and as more studios opened, the burgeoning Internet helped spread the word.

As early as 1994, U.S. News & World Report was proclaiming “Yoga Goes Mainstream.” By early 1998, Madonna was chanting om and singing Sanskrit over a techno beat in her Grammy-award-winning pop album, Ray of Light. A few months later, she was talking Ashtanga yoga with Oprah and demonstrating jnana mudra on the cover of Rolling Stone.

Celebrities such as Sting and Christy Turlington also gushed about yoga and its effects, and pics of mat-toting celebs en route to class became commonplace in tabloids. The cultural obsession with all things yoga extended to the pages of glossy magazines, including Vogue, Vanity Fair, and People. With mentions of it everywhere, yoga was suddenly part of pop culture.

The vigorous styles of yoga that were becoming popular by the early 1990s enabled many of us to discover a spiritual practice through a physical one. Yoga offered a moving meditation, a centering contentment, and a life-changing self-awareness to millions—one that many of us hadn’t known we needed.

As teacher and writer Anne Cushman mused in an issue of Yoga Journal from that decade, “Unless you’ve been in a very deep Savasana for the last year or so, you’ve probably noticed: Yoga is chic.”

This was an era of dynamic change, and the ways in which yoga and America intersected as the decade continued were complicated. The practice was no longer considered niche, yet its adherence to tradition could be questioned. Scandals concerning well-known yoga teachers began to come to light, even as other topics, including cultural appropriation and lack of accessibility, were left in darkness.

Stretching Past Old Stereotypes

It was during this cultural moment that my roommate saw a flyer for a yoga studio on Fifth Avenue.

I was drawn to the spiritual aspects that the promotional postcard promised, while my roommate was seeking calming and stretching. With curiosity, we shyly unrolled our rental mats in the back row of the studio. That’s when we realized we’d accidentally attended an “intermediate” class as total beginners. Tripping our way through Sun Salutations and glancing around during breathwork to see what others were doing, we looked at each other and laughed. What had we gotten ourselves into? I felt completely lost, yet somehow, by the end of class, I also felt found.

Like many Americans during this decade, I didn’t entirely understand the effect that yoga had on me, although I liked it. So I came back. Again and again. As different lineages and styles of yoga—Ashtanga, Jivamukti, Power—became increasingly common stateside, I was curious to learn more and went from studio to studio throughout Manhattan.

Jivamukti

If yoga reflects the culture and time in which it’s shared, there was definitely an East Village ethos to Jivamukti—a blend of punk, art, and spiritual seeking commonly found in the downtown set.

Jivamukti differed from many styles of yoga by overtly combining the physical side with the spiritual side. It was built upon what founders Sharon Gannon and David Life learned from teachers Pattabhi Jois, Shri Brahmananda Sarasvati, and Swami Nirmalananda. Yet it revolutionized tradition by setting the poses to contemporary music, such as David Bowie and The Rolling Stones. The demanding classes included chanting in Sanskrit, sometimes led by musician and vocalist Krishna Das, amid talks on veganism and walls painted with Hindu deities.

It was a young scene, mostly white, sometimes with celebrities such as Willem Dafoe in attendance. By 1998, the popularity and ever-expanding student base of Jivamukti Yoga Center prompted Gannon and Life to move their East Village studio to a larger space on Lafayette Street. The blend of pop music, sweaty movement, chanting, and spirituality infiltrated yoga culture and vinyasa classes around the US, melding the contemporary cultural moment with the ancient tradition.

The practice also did a very ‘90s thing by catching press. An article in New York Magazine mentioned their interfaith approach to spirituality and explained that “Jivamukti comes from Jivanmukti, Sanskrit for ‘liberation of the soul.” It asserted that there is an emphasis on making the practice open to “all.” This was well-intentioned although ironic given the largely white student base at this and many studios.

Ashtanga Yoga

Ashtanga yoga, as taught by Sri K. Pattabhi Jois, is an athletic and ritualistic style of yoga. It comprises a set sequence of poses, always taught in the same order and usually taught with very little instruction other than the counting of breath. There are six memorized sequences, each known as a series, and students are allowed to progress to the next series only with the teacher’s authorization.

In 1993, YogaWorks co-produced an instructional video teaching the Primary Series, or the first series, as led by Jois. Many teachers who studied directly with Jois in India became leading teachers in the States around this time, including Maty Ezraty, Chuck Miller, Richard Freeman, Tim Miller, Eddie Stern, and more. It eventually gave rise to what we know as vinyasa as well as Power Yoga.

Power Yoga

Power Yoga creator Bryan Kest was a student of Ashtanga who had studied in India and practiced Vipassana meditation, which included donation-based retreats and offerings, and eventually brought all this into an innovative approach to yoga.

During the classes I attended in Los Angeles, Kest explained that “power yoga” was named to celebrate cultivating an inner power and finding focus through mindful movement. Kest typically led classes without music. He focused more on meditation and deceptively simple shapes that empowered the individual toward self and cosmic knowledge. He also shared modifications for poses long before the concept of accessible yoga was commonplace. In 1995, Kest recorded a series of Power Yoga videos with Warner Brothers.

Further up the coast, Baron Baptiste began studying various styles of yoga at age 12. The son of two longtime teachers who opened the first yoga center in San Francisco, Baptiste created his own intense style of power yoga with intense holds in a heated studio. He called it Baptiste Yoga.

The hot approach was not entirely unlike what was taught by one of Baptiste’s teachers, Bikram Choudhury, who had become prominent in Los Angeles as the yogi to the stars for his sequence of 26 postures practiced in a heated room. His attempt to copyright the sequence would be denied by federal courts.

Other influential Power Yoga teachers of this time include Beryl Bender Birch, who evolved her version of the practice from her longtime studies in India and practice of Ashtanga. She also wrote the best-selling book, Power Yoga, in the mid ’90s.

Kundalini Yoga

Gurmukh Kaur Khalsa began teaching Kundalini out of her home in 1992. A white woman teaching out of LA and NYC, she took teachings that she’d learned—in her case, from Yogi Bhajan—and attempted to make it more approachable to a contemporary audience. Her approach to Kundalini later became the basis for her studio, Golden Bridge Yoga, originally based in Hollywood and later in New York. With her focus on breathwork and kriyas, or practices, all done while wearing a white turban, she introduced subtle body work to many Americans. During my phase of yoga exploration, I attended several of her classes, sitting in the back of the room, breathing with my arms raised, amid others, many dressed in white, all of us practicing self-awareness.

Dharma Yoga

And there was Dharma Mittra, who began teaching yoga in Manhattan in 1975 at his Yoga Asana Center which later became the Dharma Yoga Center. Classes were physically demanding yet based on the slower and more internal practices of yoga nidra and meditations.

I loved Dharma’s classes. On Fridays in the late ’90s, I’d schlep to Dharma’s studio for his signature Psychic Development class, which felt like a step further into yoga and all its limbs than some classes that seemed to be exclusively asana. There, I chanted a different single-syllable mantra for each chakra, engaged with various forms of breathwork and meditation, and visualized exploring the subtle body. For days afterward, I’d feel clearer and more connected to my intuition.

Yoga Turns Commercial

As the styles of yoga and numbers of students surged, capitalism responded.

Historically in India and elsewhere, physical poses were explored on towels, rugs, or bare floors. To practice yoga, all you needed was your body. That changed in the ’80s, when teacher Angela Farmer thought to cut foam carpet underlay into rectangles for cushioning. But it wasn’t until 1990 that contemporary yoga mats as we know them were devised and popularized, beginning when Hugger Mugger manufactured what it dubbed the “first sticky mat.” Its non-skid surface was meant to keep students in place during hot, sweaty practices and its cushioned support intended to provide comfort in the stillness of Savasana.

Within the decade, competitor companies emerged and rolled out alternate yoga mat options that delivered varying approaches to grip, stability, comfort, durability, and sustainability. Some were made from natural rubber, such as the iconic PRO mat by Manduka, a mat and company founded by yoga teacher Peter Sterios in a move that demonstrated alternate income streams were available for yoga teachers. Many mats were fashioned from PVC, a non-biodegradable plastic, and would later come under scrutiny long after the 90s and largely be rejected by most students when more sustainable options became commonly available.

Yoga-focused clothing brands, including Lululemon and Sweaty Betty, launched during the decade, too, rendering what was worn on the mat fashionable as well as comfortable. Lululemon’s first ever yoga pants, the Boogie, was among 111 iconic items later featured in the Museum of Modern Art’s retrospective, Items: Is Fashion Modern? The pants were deemed a “paragon” of fashion for revolutionizing the world with its technical, practical, and comfortable design and fabric long before athleisure was a thing.

Yoga in the Digital World

In addition to yoga navigating the material world, there was the digital one. As the grumbling sound of dial-up technology became increasingly ubiquitous, yoga became a theme in early internet forums. Here, students and teachers could experience community outside of a studio, chatting about practice questions, leaving teacher reviews on message boards, and sharing insights on the ancient philosophy. One could also explore the larger principles of the practice via ConsciousNet, essentially “a collection of high-consciousness, high-vibration” sites, according to a 1996 article in Yoga Journal. One could say these were precursors to the yoga blogs, Instagram influencers, and online teacher trainings that we know today.

There was also the continued popularity of VHS tapes. (Hello, VCRs!) Options included that one from Yee I’d tried as well as videos by Lilias Folan, who began sharing the practice via a PBS TV show in the ‘70s, famed Iyengar teacher Patricia Walden, Kest’s Power Yoga series, and numerous others. These tapes helped democratize yoga, bringing the teachings of yoga into homes distant from urban studios, usually with soothing voiceovers and demonstrations of complicated asana (poses).

Yoga as Alternative Health

Some of the American public’s increased receptiveness to yoga in the 1990s likely arose from a co-occurring interest in wellness and alternative health. Cardiologist Dean Ornish’s books and high-profile TV appearances draw awareness to stress reduction via yoga and meditation, exposing millions to the practical health benefits of yoga and not just its spiritual aspects.

The popularization of integrative and holistic approaches to health, which drew on ancient Eastern techniques as well as contemporary Western medicine, also likely helped Americans consider yoga through a different lens. After all, yoga was not just about transcending the body but taking care of it.

The decade also saw a resurgence in herbalism and homeopathy as Rosemary Gladstar, considered a central figure in the modern herbalism movement, expanded her voice and influence during this time through books including Herbal Healing for Women. She became known as the “godmother of American herbalism” and founded the California School of Herbal Studies and the International Herb Symposium.

Legislation played a role as well. The Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 established the regulation of supplements, which enabled the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to oversee the manufacturing and labeling of herbal remedies.

The result was a boom in the supplement industry. Herbal supplements lined shelves in pharmacies. Turning to echinacea for a cold was no longer fringe, it was mainstream. Flip through a Yoga Journal issue from the mid to late ’90s and the pages are lined with ads for homeopathy products and herbal products from a botanical medicine industry valued at close to $4 billion before the end of the decade.

And then there was Deepak Chopra. A physician and pioneer in integrative medicine, Chopra burst into prominence when Oprah interviewed him about his book Ageless Body, Timeless Mind on her show in 1993. In it, he taught about the mind-body connection, drawing largely from yoga philosophy.

I read this book as a tween after seeing him on the Oprah show after school, and it drew my intrigue long before I ever stepped on a mat. An interest in holistic wellness, spiritual philosophy, and asana practice began to merge in our society—an experience shared by many during the era.

Scandals, Shadows, and Social Implications of ’90s Yoga

Though the expansive popularity of yoga in the US brought the practice and its myriad benefits to millions more people, there were shadow sides to the boom.

Lack of Accessibility

Despite the desire by many teachers to offer yoga to everyone, yoga was shared disproportionately. Many studios catered to able-bodied practitioners in urban environments who could afford the expensive drop-in or membership rates. Unerringly precise alignment was commonly emphasized. Modifications or suggestions to prioritize how the body feels over what the teacher says were almost nonexistent.

Cultural Appropriation

Although it was not yet a commonly understood phrase, cultural appropriation was also rampant. Some examples were quite public, such as Madonna’s celebrated Ray of Light album, which was critiqued years after its release for sexualization of Hindu images and mispronunciation of Sanskrit. Other instances were more subtle, such as mala beads worn as jewelry and Hindu deities seen on T-shirts along the sidewalk.

And, of course, there was the issue of equating practicing yoga poses with nothing more than a workout. The majority of yoga classes were led by white teachers and attended by white students without much, if any, discussion of its historical context. Some South Asian teachers, including Swami Satchidananda and Choudhury, drew large followings in the US during the ’90s. Yet the whitewashing of yoga continued for decades, including on the covers of Yoga Journal, before conversations about decolonizing yoga and platforming South Asian voices were heard and addressed at a level where awareness and change could begin.

Conversations examining the line between appreciation and appropriation, or celebration versus exploitation, wouldn’t take place until the 2000s and beyond. The topic remains an essential area of exploration for anyone who practices and teaches yoga, especially considering the general lack of awareness around the tradition of yoga beyond the physical.

Gurus and Abuse of Power

In the ’90s, the guru mentality reigned supreme. Teachers were expected to have all the answers and students followed blindly. This set the stage for power imbalances and sexual abuse scandals that would eventually rock the yoga world.

Public allegations of inappropriate behavior, spiritual abuse, sexual assault, and questionable teacher and student relationships were almost unheard of in an era that predated the #MeToo movement. Yet toward the end of the ’90s, victims began to find their voices. Allegations of abuse came out against prominent yoga teachers including Baptiste, Yee, Satchidananda, and others. In some cases, the public pronouncements brought about change, as when Amrit Desai resigned from his position of spiritual director of the Kripalu Center and it underwent significant transformation from a guru-centered ashram to a secular educational center.

In other spaces, the abuse continued and was only revealed in later years, such as with alleged abuse by Jois, which was revealed after his death. Choudhury would later be accused by numerous students of impropriety and sexual assault and taken to court in a civil suit for wrongful termination by a former employee. Each time news of these fallen gurus became public, students were left to question where they had placed their trust as they struggled with the need to separate the teachings from the teachers.

These years became largely indicative of how American yoga was surging in popularity but also, in many ways, needing to mature.

Profusion of Yoga Teacher Trainings

With appropriation, abuse, and an unprecedented proliferation of students enrolling in yoga teacher trainings came concern about the need for oversight. In 1999, Yoga Alliance was created. According to the organization’s website, the intention was to create some standardization in an exploding industry. Yoga Alliance was and remains a voluntary registry for yoga teachers and yoga schools who pay dues to the organization. It outlined guidelines that standardize topics taught in yoga teacher trainings and delineated who could be classified as a Yoga Alliance-registered 200-hour or 300-hour yoga teacher.

This brought a more official vibe to what had begun in the ’80s, in which learning to teach yoga shifted away from lifelong devotion and apprenticeship and toward a certificate awarded after a 200-hour training. Wisdom that had once been passed down from teacher to teacher over the course of years through immersion was outlined in a syllabus and counted in hours, something that many teachers in the ’90s resisted.

What Yoga Meant to Us All

Yoga became a part of my everyday, anchoring me in a spiritual framework that helped me make sense of life and myself. I eventually took teacher trainings and began teaching yoga to youth in NYC public schools yet I remained foremost a student. Although I still wasn’t certain what I was initially seeking all those years before, I was brought exponentially more.

As the decade drew to a close, many worried that the traditional practice had been overtaken by American consumerism. The October 1998 issue of Yoga Journal questioned whether the rising popularity of yoga was hype or actual cultural soul searching. It was a complicated question with no clear answer.

My understanding of the larger meaning of the practice’s popularity in the 1990s became apparent to me only after the fact. In the months after September 11, 2001, I saw exponentially more mats on the backs of New Yorkers as they walked the streets of NYC on their way to and from studio classes. We were sincerely searching for answers and sought refuge in a physical practice and a philosophy that could hold our unanswered questions in the wake of significant shock and grief.

I was grateful I’d met yoga. The practice that had found me where I was as a curious teen continued to find me, over and over, delivering more than I even knew I needed.

Maybe, in a way, the same thing happened for America.

Leave a Reply