We take it for granted today, but John Woo has one of the most recognizable visual signatures of any living filmmaker. Back in the mid-1980s, what started in Hong Kong reverberated around the world, as Woo — who was then stuck at the lowest point of his career — elevated action to art, finding poetry in the medium’s most destructive genre.

For many years, and for no good reason, it was all but impossible for international audiences to see the three John Woo movies that saved his career, launched Chow Yun-fat to stardom and revolutionized action cinema forever. They are, in chronological order, “A Better Tomorrow” (1986), “The Killer” (1989) and “Hard Boiled” (1992), and all three are playing in stunning 4K restorations this week at the Lumière Festival in Lyon, France, where Woo will be on hand to introduce his first three masterpieces.

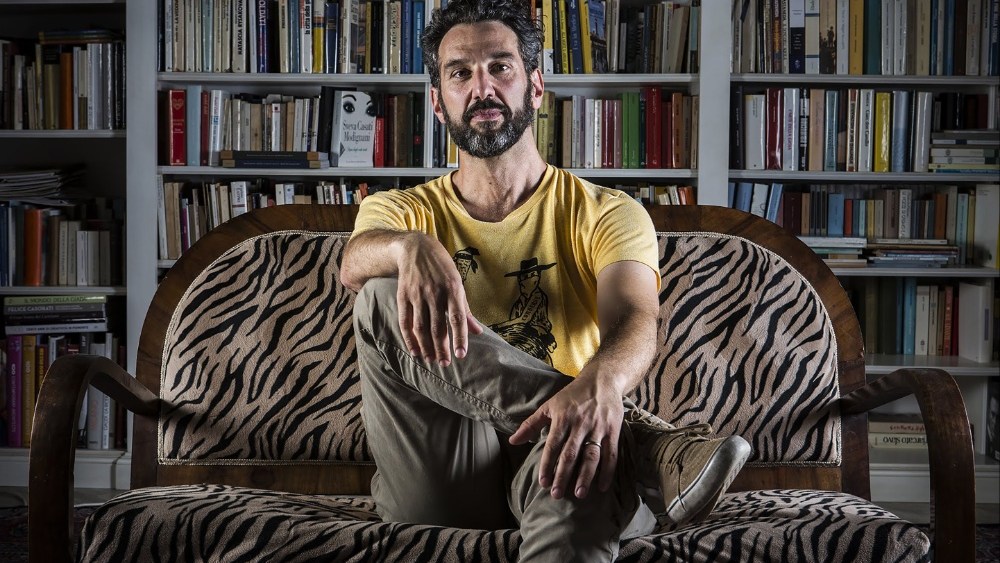

Before flying overseas, the 79-year-old legend was gracious enough to welcome me into his headquarters in West Los Angeles, which overlooks the Getty Museum. The suite offers a panoramic view of the city Woo now calls home, and yet I found myself staring at the walls, on which hang giant posters for his most influential movies.

In the corner, separated by a tall glass wall — the kind it’s easy to imagine Chow crashing through in slow motion, with guns blazing in both hands — Woo’s office is decorated with enormous posters for two classics by French director Jean-Pierre Melville: “Le Cercle Rouge,” with Alain Delon, and “L’Aîné des Ferchaux,” starring Jean-Pierre Belmondo. I can tell this is going to be a good conversation, since Melville is my favorite director, too.

“When I was young, I wrote quite a lot of poems,” Woo tells me. “I have always imagined that no matter what happens in this world, there is always some kind of beauty existing. And I also like romanticism. My style was greatly influenced by European movies, and especially Jacques Demy’s movie, ‘The Umbrellas of Cherbourg.’”

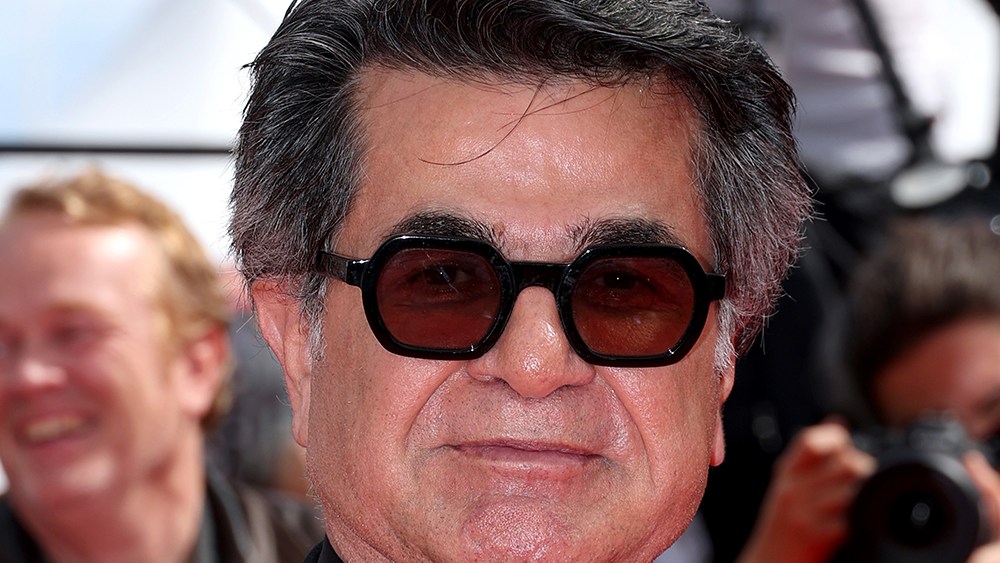

This isn’t what I expected to hear. With Woo, the connection to French crime films is clear: Melville was obsessive about American genre cinema. He studied, absorbed and ultimately improved upon the codes in such film noir classics as “This Gun for Hire” and “Odds Against Tomorrow.” Decades later, Woo did the same with Melville’s movies (“Le Samouraï” and “Le Cercle Rouge” in particular).

But a musical like “The Umbrellas of Cherbourg,” which explodes with color and ends in tears? It’s not the first reference that comes to mind.

“When I’m making an action movie, I don’t see it is an action movie,” Woo explains. “It’s like a painting or a poem, sometimes even like a musical. I’m aiming for that kind of feel, because I’m a dreamer. I think that’s my style because I always have some kind of beautiful dream in my mind.”

Woo’s first filmmaking job was working as assistant director for Shaw Brothers veteran Chang Cheh. At a time when the Hong Kong industry was dominated by sex comedies and kung fu movies, Chang taught him the principles of dynamic action. And though he never studied any of the martial arts, Woo has always loved dance, which made all the difference in how he stages gun battles.

“I was a pretty good dancer when I was young,” says Woo, who choreographs the balletic action scenes in his films himself. “When it comes to the action in a movie, it’s all about the beauty of the body movement and the fighting skill.”

In the 1970s, Woo had a successful run directing comedies and other projects that might now seem off-brand to his fans, like the 1976 Cantonese opera “Princess Chang Ping” and low-budget action comedy “Money Crazy.” That changed in the early ’80s, when Woo hit a rough patch. “My movies didn’t work at all, and then I became a box office poison,” he says with a chuckle. “I was looked down on by so many people, and some of my friends even said I should retire.”

Meanwhile, Woo’s friend and fellow director Tsui Hark was on a hot streak, which put him in the ideal position with Golden Princess, a new production company with money to spend and limited experience in cinema. Unhappy to see talented peers unable to find work, Tsui used the opportunity to produce projects for Woo and others.

“He’s a good man,” Woo says. “He liked helping the others, so if he saw anyone out of a job who couldn’t get a movie, he supported them.” It was Tsui’s idea to make a gangster movie that a family audience could watch — what became “A Better Tomorrow” — which Tsui would produce and Woo could direct.

“That was my first auteur film,” Woo recalls. “He encouraged me to put myself into the movie, to make the movie my own. And he let me change all the dialogue, to say what I really wanted to say from my heart.”

For years, Woo had been wanting to make a film like “Le Samouraï,” but no one would give him the opportunity. At last, he was being given the green light to incorporate his personal style into a project, dressing Chow in a stiff trench coat — a nod to both Alain Delon and his favorite Japanese star, Ken Takakura — and giving the character a strict code of honor that would become a Woo signature. (At the time, the director felt the younger generation had lost appreciation for traditional morals, so he designed the dynamic between Chow and Ti Lung’s characters — which reminded Chinese audiences of the bond they felt toward old schoolmates — to reinforce the values of brotherhood, friendship and sacrifice.)

“Before ‘A Better Tomorrow,’ I didn’t have much chance to try this kind of a style. Because I never got any support from the studio or anyone, I wasn’t able to experiment,” he says.

Working with Tsui for Golden Princess was different. So long as the films were profitable, the financiers left them alone.

“We had a lot of creative freedom,” Woo remembers. “There was a trust between us, so we could do whatever we wanted, so every director, they had a great opportunity to try something new, something they had never done before.”

As far as the investors were concerned, Tsui and Woo knew the market. By keeping the budgets tight, they could be reasonably sure the films would break even — and many were wildly successful (“A Better Tomorrow” broke all box office records in Hong Kong, prompting a sequel, even though Chow’s character had been killed in the original).

“Since we were trusting each other, there was no need to give them a completed script. We just let them know the idea, the rough budget and the shooting schedule,” Woo says. “Their main concern was about the casting, if you can find somebody who could guarantee you make money.”

Working for Chang back in the day, Woo had watched his mentor turn unknown actors into stars. And of course, he had developed his own strategies over the years. “I know how to use all kind of tools to help the actors,” he says. “I know what kind of lens will make him look good and what kind of angle. And the size will bring out his very special quality.”

With Chow, Woo saw something in the actor (who was a popular TV star, but nothing on the level of what followed) no one else had. Watching a show called “The Bund,” Woo noticed how the actor’s eyes helped tell the story and cast him against type as a triad gangster given a chance to redeem himself.

“He had never punched a guy in his whole life,” says Woo, who tailors the action to each actor he works with. He might try to find out what sports a given performer prefers — like running or swimming — and then model his movement accordingly, incorporating that into his choreography. Woo even considers the size of his actors’ trigger finger when selecting the right guns for them to use in a shootout. “If he’s got a long finger, then he could be holding a little bit bigger guns. If he has a short finger like me, then he’ll hold a pistol, not too long.”

One of Woo’s signatures — actors holding two handguns, firing with both barrels at the same time — has an unexpected origin. “I’d seen a lot of Westerns,” Woo says, but he wasn’t thinking of cowboys with holsters on each hip. On “A Better Tomorrow,” he wanted to shoot the definitive gun battle in Hong Kong movie history, but Woo figured, “if he’s a professional killer and he’s a true hero, he would never use a machine gun. It’s too easy and not elegant.”

Woo had a clear idea of the sound he wanted — he could hear the drumbeat in his head — but had never owned a gun in his life, so he asked the props team for help. The weapons experts suggested a semiautomatic Beretta 92F handgun that could fire up to 15 rounds nonstop, though the tempo wasn’t fast enough. Then Woo had an idea: “How about using two guns?” By staggering the rhythm, where Chow alternated pulling the trigger with each hand, Woo got the “music” he wanted.

“A Better Tomorrow” was a huge hit in Hong Kong, which gave Woo a chance to make several more movies for Golden Princess. He had even more creative control on “The Killer.” Tsui was busy producing other films at the time, leaving Woo to do what he wanted — which, in this case, was a poetic hitman movie, à la Melville’s “Le Samouraï,” where an assassin sacrifices himself for the lounge singer who witnesses his crime.

“I had the whole movie in my mind,” says Woo, who shot without a script, instructing the actors and crew what he wanted with each scene on set. According to the director, they thought he was making another “Better Tomorrow” and weren’t expecting something so romantic.

When “The Killer” was invited to screen at the Toronto Film Festival, Woo was instantly recognized as a visionary talent by international critics. The director’s most bombastic movie by far, “Hard Boiled” made him an even hotter commodity abroad. The plot was inspired by a Japanese news report that had deeply disturbed Woo, about a lunatic guilty of poisoning baby formula. Ever the moralist (despite the level of violence in his films), Woo flipped the idea to focus on two cops who wind up protecting innocent hospital patients — including a ward full of newborn babies — from a ruthless triad boss.

“What surprised me was how it got such a warm welcome from the Western world,” says Woo, who started to get offers to work in Hollywood.

“The biggest reason I came to Hollywood was because I wanted to learn something new. At the same time, I tried to prove my style could also work in a Hollywood movie,” says Woo, whose signature techniques — slow-motion cinematography, gravity-defying choreography, over-the-top pyrotechnics — were already influencing Western directors like Robert Rodriguez and Luc Besson.

Woo wasn’t quite prepared for how much stricter the American industry was about everything, from second-guessing the director to how violence is depicted. (His first Hollywood feature, “Hard Target,” earned an NC-17 rating on that front.)

In America, Woo observes, “The studio and the big star had so much control. They have final approval of the script and the supporting roles. But in Hong Kong, the director is everything.”

On “Hard Target,” Belgian bodybuilder-cum-action hero Jean-Claude Van Damme wanted a say in how Woo cut the footage. The Hong Kong helmer was lucky to have producers Sam Raimi, Jim Jacks and Rob Tapert in his corner. “When the star tried to control the editing, they threw him out,” he says.

Woo’s best American studio experience was making “Face/Off,” which had been conceived as a more overtly sci-fi scenario set 200 years in the future. Woo wasn’t comfortable with that genre or the visual effects it would have required, so it was rewritten as a more contemporary “human drama” (in Woo’s words).

What made it so satisfying, apart from all that stars John Travolta and Nicolas Cage brought to their characters, was having the full support of Paramount chairman Sherry Lansing. The way Woo tells it, Lansing gathered the entire crew at the outset and told the room, “All I want is a John Woo movie. So no one should give him any notes.”

But there was a harsh trade-off for all the creative freedom Woo had enjoyed in Hong Kong: Golden Princess owned the rights to all the films he and Tsui had made, which they parceled up and sold to different territories. Then the company went under, and the films fell out of circulation in most parts of the world. “So the Hong Kong movies we had made became just like a memory,” says Woo, who’s delighted to see them finally restored and back in circulation, since Shout! Studios acquired the Golden Princess library earlier this year.

The reason Woo was able to remake “The Killer” last year can be explained by a fluke over film rights: Nearly three decades ago, Columbia had wanted to do an American “cover” version, but couldn’t get it off the ground. Many screenwriters and directors had come and gone from the project, without success.

“It never came together. And then after 20 years, they gave the rights back to us,” Woo says. He was working in China, shooting “Red Cliff” at the time, but he was intrigued by Brian Helgeland’s idea of gender-flipping the killer, so Chow Yun-fat’s character would be a woman.

“When I came back, I really got excited, because I had never considered a female killer before,” he says.

According to Woo, his biggest regret about the Golden Princess period — and the film he’ll never be able to fully recover — is 1990’s “Bullet in the Head” (the film he made between “The Killer” and “Hard Boiled”).

“The original cut was three hours, but for the Hong Kong release, I was forced to cut it down to two hours,” he explains. Woo had to slash several scenes he was proud of to appease the producers. Once Woo came to Hollywood and had earned enough money, he tried to buy the rights to the movie, but it was too late: The Hong Kong lab that held onto the deleted footage had thrown it out after a year. “They only get saved for one year, and then they are thrown away like garbage,” he says.

The good news is that Woo’s other Golden Princess projects have survived and can now be rediscovered by audiences who grew up on “The Matrix” and the John Wick movies.

Leave a Reply