I’m all for a documentary that celebrates its subject, but “Stiller & Meara: Nothing Is Lost” is a movie that takes what it’s about and holds it up to the light with such unbashed reverence that after half an hour or so, I thought it was all going to be a bit much. Actually, it turns out to be a very good film — canny and honest and unexpectedly moving. But it’s layered with a thick and sugary frosting of adoration.

The movie is a portrait of Jerry Stiller and Anne Meara, the husband-and-wife comedy team who first came to prominence on “The Ed Sullivan Show” (they made their debut appearance there in 1963) and then became a popular nightclub and TV-variety-show act in the ’60s and ’70s. Stiller and Meara were quite successful, but I wouldn’t call them superstars. I used to see them on TV when I was growing up, and it doesn’t take long for the film to capture the sweet-and-sour novelty of their stand-up sketch-comedy repartee — the way their affectionate but spiky interchanges, rooted in the stark contrast of their personalities (he was a Jewish crank who was like the missing link between Alan Arkin and Al Goldstein; she was a sunny Irish lass with a tart tongue), looked ahead to the age of “Annie Hall.”

We see a telling clip of Johnny Carson, sometime in the late ’60s, saying, “They’re married in real life! He’s Jewish and she’s Irish — for real,” and his eyes light up with amazement. That’s how unusual it was, at the time, to see a showbiz couple drawn from such different wells. That said, Stiller and Meara, while they had a fresh and even trend-setting image, always came off, at least to me, as a likable but rather lightweight comedy team.

As the documentary captures, there was an edge of conviction to their act, because they drew it from their own lives, and their love and (at times) acrimony would spill right onto the stage. Yet Stiller and Meara were launched in the pre-counterculture era of Nichols and May and Mel Brooks’ 2,000 Year Old Man, and by the time they became a TV staple, there was something a tad corny and dated about them. In the documentary, we see their two greatest routines, a satire of computer dating that they first performed in 1966, and their “Hate” sketch, which was way ahead of its time. But once you’ve chuckled at those, there isn’t much left to discover about them as comedians.

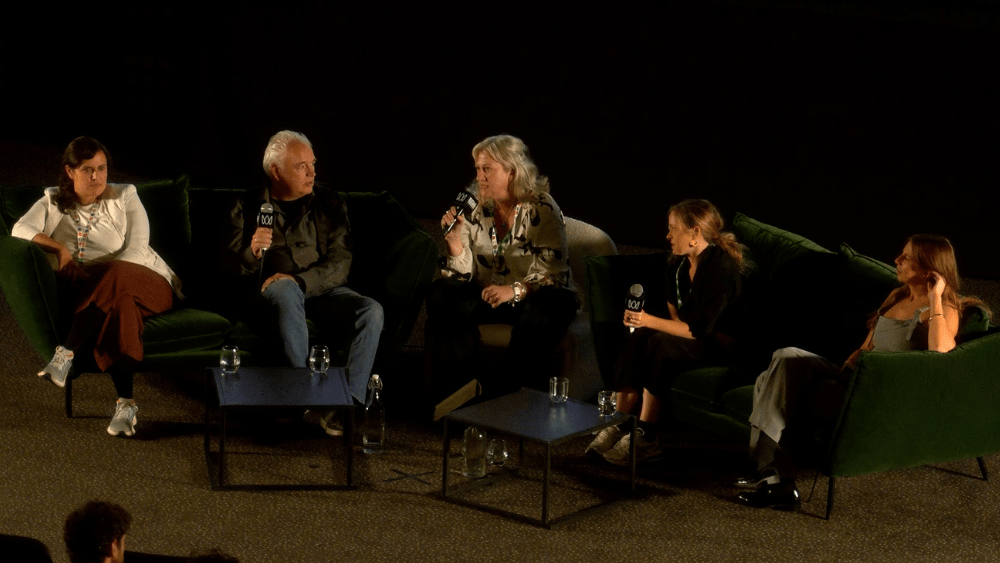

It’s hardly a surprise, though, that “Stiller & Meara” treats the two of them like gods on the comedy Olympus. The film was directed by Ben Stiller, who is their son, so yes, he’s a bit close to the subject. What he’s put together has to be reckoned a definitive look at the career of Stiller and Meara. At the same time, the documentary is a tender but clear-eyed family portrait. It was shot starting after Jerry’s death, in 2020 (Anne Meara died in 2015), and much of it consists of the lean, warm, now silver-haired Ben Stiller and his curly-haired acerbic older sister, Amy, hanging out in the vast Upper West Side apartment on the corner of Riverside Drive and W. 84th St. in which the two of them grew up, and where their parents spent most of their lives together.

The apartment is jammed with memorabilia and bric-a-brac, because Jerry Stiller was a pack rat when it came to recording his life — he was into taping conversations, he always had a camera out (that’s how Ben first started to make films as a kid), and “Stiller & Meara” shows us a lot of this stuff: the home movies, the diaries, the personal notes, the recordings of the everyday. (It’s this that the film’s rather bland subtitle, “Nothing Is Lost,” refers to.)

The family comes off, relatively speaking, as quite a happy foursome. It’s clear throughout the documentary that Jerry and Anne genuinely loved each other, and that they provided a nurturing and creative environment for their children. Ben and Amy recall their parents with a richly amused understanding of the couples’ foibles (especially Jerry’s, since he practically wore them on his lapel), and while it’s nice to see a high-powered showbiz family that seems so well-adjusted, a part of us is going: Okay, fine, where’s the drama? Even when we learn that Anne relied on alcohol to cope with the stresses of their performance life (they would go to Patsy’s Italian Restaurant on W. 56th St. and she’d have her vodka), the film makes a point of not overstating the dark side of her addiction. (On a tape of Anne talking to Jerry after a night of this: “I drank too much. I drink. It’s not the end of the world!”) Anne liked her vodka but held herself together and appears, in hindsight, to have been a woman of joy and well-being.

Midway through the movie, having absorbed all this (and sensing that there’s not going to be any dark bombshell), I thought: What is there left to tell? But that’s just when “Stiller & Meara” begins to morph from a likable entertainment-world profile into something more resonant — a nearly novelistic portrait of Jerry Stiller and Anne Meara’s life-and-art marriage. In the grand scheme of things, it was a happy one, but it was complicated. They had tons of fights and temperamental clashes. One reason they were two peas in a pod is that their backgrounds were more alike than we imagine: Jerry was born and raised in New York City, whereas Anne was a self-described “Irish princess” from Long Island. She retained a dollop of that Lawn Guyland accent, which is one reason words like “meshuggenah” rolled off her tongue. They may have been from different tribes, but they were both tribal.

Here’s something I picked up on: As successful as Stiller and Meara were, had they been more successful — more famous, more coveted, a bigger act rather than a variety-show fixture — they would likely have gotten divorced. Celebrity and money would have been poured onto their simmering tensions like gasoline, and they would have detonated. In their act, Jerry was arguably the less gifted of the two, but he was the perfectionist (mostly because he was so insecure about his talent), and that took its toll. It drove Anne nuts, because she was actually less invested in their success.

And maybe that was her way of keeping them sane. Since Stiller and Meara were stars who weren’t overly famous, they were able to keep their professional lives in a kind of compartment. And this allowed them to put family first. That they did so was rather heroic, as well as charming and touching. They would parade their kids onto talk shows (there’s a hilarious clip of Benjy and Amy on “The Mike Douglas Show” playing “Chopsticks” on violins), but it’s also fascinating to behold how when the two did on-camera interviews, they would discuss their lives, and it would suddenly get very serious, and their disagreements would rise to the surface, only to be channeled into a laugh (though not always), which became a form of therapy. Later on, we learn that they underwent plenty of couples’ therapy.

To complete the family meditation, Ben Stiller puts his own children, Ella (23) and Quinlin (20), on camera, as well as his wife, Christine Taylor, from whom he was separated for several years (the two reconciled during the pandemic). He talks about how much his own flaws echo those of his father, but the truth is that Ben Stiller comes off here as such a benign and accommodating person that the family-demons-through-the-generations theme doesn’t register with very much impact. It just gets filed under “Nobody’s perfect.”

In the ’70s, Stiller and Meara began to pursue separate careers as straight actors (that’s how Anne had begun), and they had some real success, with Jerry appearing in movies like “The Taking of Pelham One Two Three” and “Airport 1975” (which inspired young Benjy, with a home-movie camera, to make “Airport ’76”), and Anne in “Lovers and Other Strangers.” In 1975, each of them was tapped to star in a TV series (Jerry in the sitcom “Joe and Sons,” Anne in the law drama “Kate McShane”), and it was probably part of the karma of their long-term harmony that both shows failed. They were married for 62 years.

Jerry Stiller finally found a kind of mega-fame when he was cast as George Costanza’s disgruntled father on “Seinfeld” — the most perfect casting in the world, since even back in the 1970s he sounds like George Costanza’s father. In the documentary, Ben and Amy say that Jerry seemed to bring all his buried sides, the anger and the craziness, to that role. Yet Ben describes his father as a “spiritual” man, in a way that remained hidden from the camera. Anne Meara, on the other hand, was all soul — the kind of person who was visibly generous, though when we hear her on the tapes Jerry made of their conversations, you saw that she gave as good as she got. Neither one was a doormat; neither one was a saint. Yet they remained devoted to each other, and “Stiller & Meara” shows you, quite movingly, that what the two had in common was how ardently they both believed in something bigger than themselves.

“Stiller & Meara: Nothing Is Lost” streams on Apple TV+ starting Oct. 24.

Leave a Reply