On a late summer morning in the Pacific Palisades, dozens of hummingbirds rise from the ashes of Spencer Pratt‘s scorched hillside property, where his 2,200-square-foot, three-bedroom home once perched. “This is how much I didn’t believe my house was going to burn down on the day of the fire: Instead of packing up, I was changing my feeders, putting in fresh nectar,” he says of the hovering flock, which he’d long tended before his hometown’s historic destruction.

At 42, the onetime reality television villain turned content creator and energy crystal purveyor is now in his unlikely third act — emerging as a zealous crusader against those he believes failed to protect the Palisades from the January wildfire that consumed it. The hummingbirds are one of the few subjects that, briefly, softens him. “They’re just magical,” he says. But for the most part, he radiates with unrelenting rage.

Visits to what was once their home trigger contrasting emotions in Pratt and his wife, Heidi, who together found fame on MTV’s hit 2000s reality drama The Hills. “She comes here and cries a lot,” he says. “I come here and get really angry. To me, it’s a power source. I’m just fuming right now — we should be sitting in our living room.” He adds, “Everyone processes trauma differently. I’ve tried to channel all my emotional energy into accountability and just making it so clear that this was preventable.”

To Heidi, who shares her husband’s frustrations but directs her own focus toward their resettled family life in the Santa Barbara area, his outspokenness in “standing against the machine” is “heroic and inspiring. He’s going beyond himself. He’s being such a good influence. He’s being such a good example for his children.”

Those long familiar with Pratt’s clownish agent-of-chaos persona both onscreen and on their social feeds may find his latest role disorienting. Now, finally, after two decades in the limelight, for once he gets to play the hero — up against an array of characters he’s cast as his antagonists.

The hummingbirds have returned due to Pratt’s diligent commitment in the months since the fire: “For me, they’re a symbol of survival. A hummingbird just does not stop.” Pratt strongly relates. “I’m just not stopping.”

***

“This is the worst thing I could be doing with my life,” he says of his advocacy. “I should be slinging my crystals.”

Photographed by Mark Griffin Champion

More than anything, Pratt wants to make it clear that the Palisades Fire — the third most destructive in California’s history, killing a dozen people and destroying more than 6,000 structures — wasn’t a natural disaster: “This was no act of God. This was an act of idiocy. This was gross negligence.” It’s a common view among Angelenos, especially Palisadians, although few have advocated for answers in the tragedy’s aftermath quite so fervently and relentlessly, or at least so publicly.

Pratt, who along with Heidi and other property owners has sued the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power for its infrastructure failures, offers many grievances. Foremost among them is what he considers the fire-fatalist attitude of officials about properties, like his own, that border wildlands: “What’s the point of paying taxes if you can’t reliably protect us? You can’t just blame climate change. It’s negligence in preparing for it.” He’s also ticked off about the unwillingness of elected leaders to quickly hold bureaucrats responsible for their failures. “If this had been a private company,” he says, “the board would’ve come in and [terminated] everybody.”

Pratt rails against the property insurance situation before the blaze and the foreign corporations snapping up parcels from distressed sellers who’d planned to pass them down to younger generations. He goes on at length about how a previous small Palisades blaze on Jan. 1 set by an arsonist was never properly extinguished, leading to the catastrophic inferno, and how firefighters weren’t adequately prepositioned in the neighborhood to respond to it. “It’s not like they didn’t know the wind was coming,” he says. (The LAFD’s after-action report identified several significant management deficiencies.)

That’s not all. Pratt has much to say about FireAid, contending that its $100 million in raised funds have been, to his mind, largely squandered. (The relief organization denies this.) Oh, and don’t get him started on the rules for private property fire protection — for everything from roofing to landscaping — when government agencies often haven’t followed their own directives for public lands in clearing underbrush and maintaining reservoirs near residential areas. “If, for a second, I truly believed this fire was not preventable, I would keep it moving,” he says.

His around-the-clock posting about the purported dereliction of duty at Democrat-managed local, county and state government agencies has attracted national Republican attention. (Today, in addition to his signature T-shirt advertising Heidi’s pop star persona, he’s donning a black cap promising California Gov. Gavin Newsom will never be elected president.) “I just get random texts — usually it’s the [Republican officeholder’s] chief of staff. People will be like, ‘Hey, I am from blah blah blah’s office. Is this Spencer?’ ” In August and September, he went to Washington, D.C., twice, meeting with U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi, her regional federal prosecutor for California, plus the heads of the Environmental Protection Agency and Housing and Urban Development. In Los Angeles, he’s visited the IRS’ criminal investigations unit about his FireAid concerns.

Republican Sen. Rick Scott of Florida held a press conference where he described touring the Palisades with Pratt and explained he was launching an expansive probe into “exactly what happened.” Soon after, Kelly Loeffler, who runs President Trump’s Small Business Administration, appeared with Pratt in the Palisades, writing approvingly afterward on X that he’s “using his platform to demand answers” and that she’s “proud to join him to hold CA officials accountable.”

Pratt, in the pool at his parents’ Palisades property, grew up in the neighborhood. Their home also was destroyed in the fire.

Photographed by Mark Griffin Champion

***

Pratt bristles at the idea that he’s become an “activist.” To him, that’s “somebody on a watchlist. When I hear that, I don’t identify. I see myself as someone whose house got burnt out and I have a social media account to talk about it.” He’ll allow “advocate,” although he prefers “taxpayer.”

Pratt, who demurs about the contours of his personal politics, also balks at any notion that he’s a partisan, much less a Trump-era tool of partisan warfare. “If Newsom and [Los Angeles Mayor Karen] Bass were Republicans, I’d be doing the exact same thing: spitting facts,” he says, pointing out that the Palisades voted for Kamala Harris by a wide margin in the most recent presidential election. “So, I’m actually fighting for mostly Democrats who lost their homes in this community.” Asked about conservative billionaire developer Rick Caruso — the past and possibly future L.A. mayoral candidate and potential California gubernatorial contender whose Palisades retail center survived the fire — he vows, “I’m not getting behind anybody in politics. I would say I love [Caruso’s Montecito luxury hotel] Rosewood Miramar.”

More broadly, Pratt is appalled that anyone might suspect a well-known hustler is, in this case, anything but a pure-of-heart campaigner for the public interest. He repeatedly underscores that his fight is a net negative. “I should be slinging my crystals and Heidi’s music,” he says. “This is the worst thing I could be doing with my life.” Pratt adds, “All this stuff I’m doing, flying to D.C., it’s out of my own pocket. That’s the reason I’ve sold Spencer for Governor shirts.”

As further proof, he points to his self-restraint as an influencer during COVID lockdowns, which he detested. “Did you see me actively going after that?” he says. “It destroyed my crystals business. It ruined the Hills reboot. Was I [publicly] fighting Newsom then? That would’ve been a great time. I just ate all of that.”

Pratt has been asked to leverage his social media audience — more than 4 million followers across the major platforms — to speak out about accountability issues involving the wildfires in Altadena and Maui. He’s declined, explaining, “One thing I’ve learned, being famous and unfamous, is: Stay in your lane.” Yet, increasingly, Pratt is unleashed. In September, he wrote on X, “I wish fauci was in a black site.”

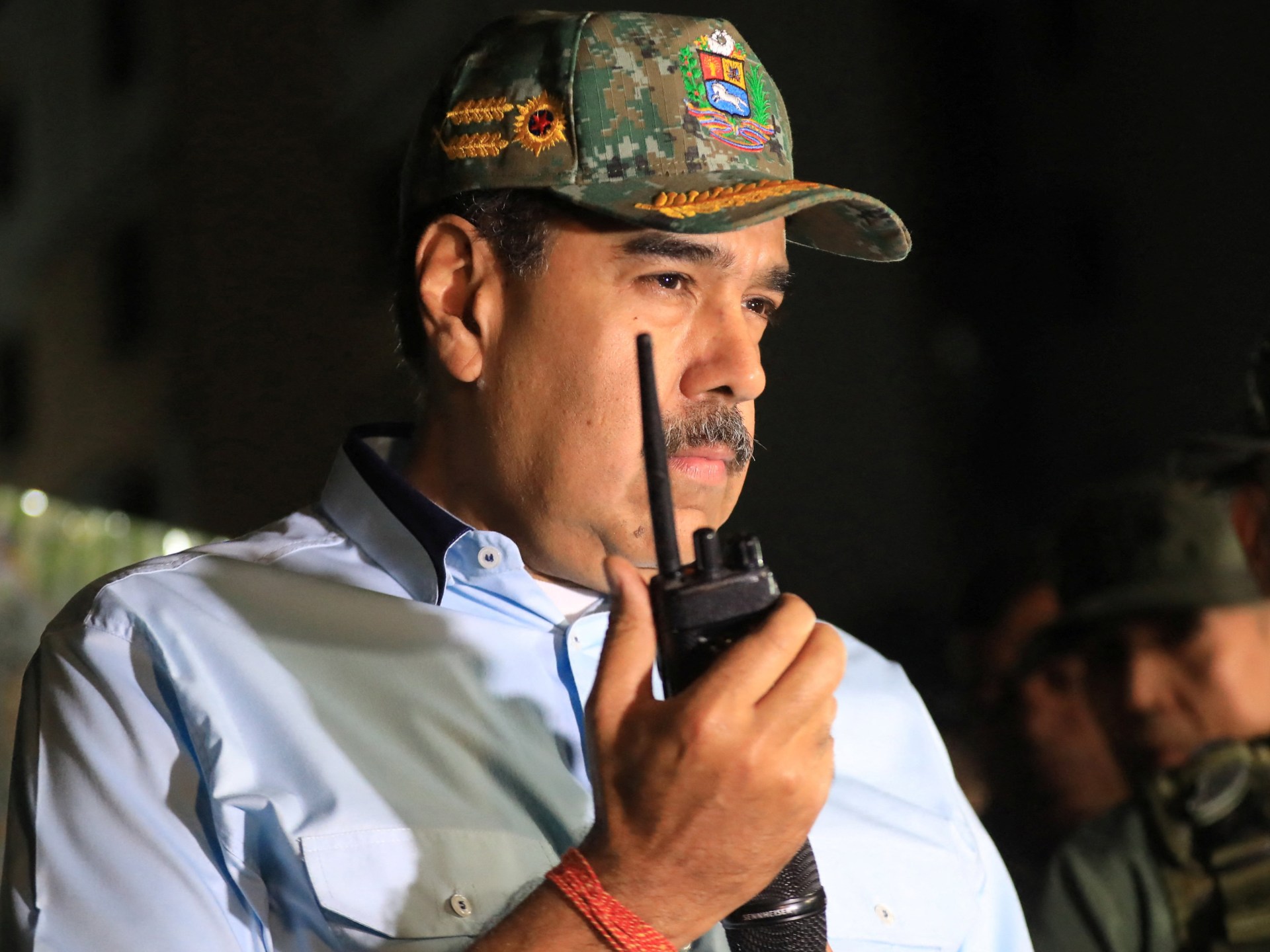

Though Pratt says he’s nonpartisan, his antagonism toward California Democrats has earned him many fans among Republican lawmakers like Florida Sen. Rick Scott (center).

Tierney L. Cross/The New York Times

Pratt’s activity has already had policymaking consequences. This summer, his critical online commentary about a proposed bill on wildfire rebuilding — the fact-checking outlet Snopes declared “the primary thrust of the claim is inaccurate” — led to its loss of momentum and withdrawal from the state legislature. Newsom called the episode “disgraceful.” Soon after, Pratt railed against a separate floated initiative for denser housing, and Newsom wound up relenting with a carve-out for fire-prone areas.

California’s Democratic establishment disdains Citizen Pratt. Bass recently told The New York Times that he’s “lashing out and creating confusion.” Newsom’s deputy communications director posted a vintage The Hills-era photo of Pratt next to an unflattering recent one, writing, “Are we sure this guy is even him? I think it’s a bad body double.” Pratt responded: “I’m sure my appearance would look better if Newsom hadn’t let my town burn down. … Stress alone has taken years off my life.”

Meanwhile, Democratic State Sen. Henry Stern, who represents a swath of the southern San Fernando Valley, linked on Instagram to a 2010 blog post about how Pratt was supposedly kicked off The Hills, in an apparent effort to discredit him. This prompted a rebuttal on Pratt’s own account: “The article he’s referencing is filled with lies, from claiming my wife fired me as her manager (absolutely false) to implying I threatened a female producer on The Hills with violence,” Pratt wrote on Instagram. “This producer had just suggested I punch my own sister in the face to boost ratings. When I refused, she mocked me. Security was present throughout this incident. No one’s safety was ever in danger, and I never threatened anyone. If these allegations were true, why did I leave The Hills with a $1 million payout from the network?”

Gabriel Mann, a wildfire documentarian who has partnered with Pratt on an in-the-works film about the Palisades disaster, thinks it’s “unfortunate” that Pratt’s accountability efforts have been politicized. “Spencer would meet with anybody that wants to help,” he says. “If [California Democratic Sens.] Alex Padilla or Adam Schiff wanted to talk to him, he’d do it in a heartbeat. But they don’t want to touch it.”

***

Pratt on his Palisades property during the fire. “What’s the point of paying taxes if you can’t reliably protect us?”

MEGA/GC Images/Getty Images

Pratt grew up in the Palisades, hanging out at the beach, hiking the trails, ordering a French dip and matzo ball soup at Mort’s Deli after weekend sports competitions. His parents’ house, less than a block from the bluffs, was brought down to its foundation, too. All that’s left is the pool, which his father, a dentist, has since cleaned out. They now live in a rented apartment in Santa Monica. Surveying the leveled neighborhood from their property, he deadpans, “Now they’ve got an ocean view.”

Pratt knows the Palisades doesn’t easily engender sympathy. Before paradise was lost, it could seem irritatingly Edenic to outsiders. What’s more, over the past decade, it went from an affluent neighborhood to “a whole new tier” of ultra wealth. He sees himself speaking for old-guard residents, comprising the mere upper-middle-class as well as non-A-list stardom. “That’s the community that I fight for,” he says. “They went to Ralphs, maybe Gelson’s. Not Erewhon.”

Pratt had taken immense pleasure in raising his sons, ages 8 and 2, in his hometown. “They went to my preschool,” he explains. At another moment, he recalls watching live security-camera footage of his sons’ bedroom ignite. “It was just surreal.” His voice catches. “This is where I’d tuck them in.”

The couple at Mercedes-Benz Fashion Week in Miami Beach in 2007, during the height of their Hills era.

Evan Agostini/Getty Images

The couple had insurance under the California FAIR Plan, which provides basic financial coverage to high-risk properties. The money is nowhere near enough for them to rebuild. “Most people we know [in the same circumstance] have already just given up and moved,” he says.

They’ve had an unscripted show in development about their family for a couple of years. “Technically, we are still alive at Hulu,” says Pratt. “I’m told by my fearless team at WME that not being passed on is a success nowadays.” He pauses, downbeat. “Hulu has the Nader sisters now,” referring to Love Thy Nader, which follows the titular siblings’ love lives and modeling adventures in New York. “They seem to have a lot of fun things going on.” Pratt shrugs. “It was positive when Heidi was touring the world with her music this year; you don’t just have to follow us crying in our dirt lot.”

The Hills persists as a sour subject for Pratt, not just because he’s experienced the long-term consequences of receiving the villain edit (“I didn’t think there would be a permanent cloud”), but because he believes that he and Heidi haven’t benefited as they should from the success of its streaming afterlife. “If I was ever going to identify as an activist, it would be in a fight for [unscripted] residuals.” He continues, “People have told me, ‘I just rewatched The Hills to support you!’ I’m like, ‘Don’t do that!’ “

Pratt’s eldest son has yet to display interest in the show that launched his parents’ careers. But he’s a fan of their subsequent stint on I’m a Celebrity … Get Me Out of Here!, the jungle-set competition that riffed on survivalism. “He loves bugs,” Pratt says, “and he watched Heidi eat that rat’s tail a hundred times. He thought it was the best thing ever.”

After finding fame (and infamy) on The Hills, Montag and Pratt embraced their roles as reality stars, appearing on shows like Celebrity Weakest Link

Greg Gayne/FOX

The couple recently launched a video podcast called The Fame Game — “because we’re all playing it,” he explains of the name. It was first conceived as a featherweight forum for pop-culture discourse, to be taped at their three-bedroom home (purchased for $2.5 million in 2017), in front of their prized his-and-her Martin Schoeller photo portraits. Post-fire, the location has stayed the same. But the shoots are now held under a scrim outside at their burnt-out lot, the backdrop a spray-painted HEIDIWOOD on a retaining wall. (It’s the name of her second studio album, released in May.) “I’m like, ‘We are paying for this fricking mortgage,’ ” Pratt says. ” ‘We are going to use this property!’ ”

Early episodes of the show have contained multitudes. The Fame Game has welcomed former Los Angeles County Sheriff Alex Villanueva, himself a polarizing political figure. (Pratt decries “[Jeffrey] Katzenberg and his dark money” for Villanueva’s 2022 electoral loss.) Another episode featured Pratt’s indignation that Heidi wasn’t asked to perform at the Jan. 30 FireAid benefit concert. Plus, there have been more personal revelations, such as how Pratt is suffering from eczema induced by fire debris toxins. He says he’s been battling this by focusing on his gut health: “drinking kombucha all day long and eating probiotics.”

Up next, in a few weeks there will be a reprieve from “this nightmare.” Pratt is scheduled to shoot “a very artsy indie film” directed by James Franco, who has been largely absent from mainstream Hollywood after accusations of predatory behavior. His role: “Playing myself.” Then, in January, Simon & Schuster will publish his memoir, The Guy You Loved to Hate: Confessions From a Reality TV Villain. “If my book’s a No. 1 best-seller, maybe I can rebuild. I just want to be back in my house, feeding my hummingbirds, making my TikToks, going on reality shows. I loved my life.”

Spencer Pratt finds it as discordant as anyone else that Spencer Pratt has, this year, become best known for sounding off about public policy. Now that he feels satisfied that he’s whipped the federal government into watchdog action, he plans to spend far less time posting about it. “I’m so sick of talking about this stuff,” he says. “I’m ready to jump back to talking about Dancing With the Stars.”

This story appeared in the Oct. 15 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Leave a Reply