All you need to make a movie is a girl and a gun. Cameras, actors, and locations help as well. Scripts are, of course, totally optional. What is really required, however, is passion and determination. Jean-Luc Godard has these qualities in abundance. It’s 1959, and he’s just watched his fellow-critic-slash-obsessive at the esteemed magazine Cahiers du Cinéma, François Truffaut, debut his first feature The 400 Blows at Cannes. Godard has some shorts under his belt. But he’s the last of his gang at the journal to go from writing about films to creating them — Claude Chabrol has already made two of them, the bastard! And Eric Rohmer has also written a novel! The young, hungry Parisian with the sunglasses and the bottomless reservoir of pithy maxims is more than ready to make his mark.

Thankfully, Godard knows a number of fellow obsessives and some guys with dough who are willing to help him achieve that goal. His buddy Truffaut even has an idea about a would-be French gangster who gets into hot water, based roughly on the true-crime tabloid story of Michel Portail. Both a girl and a gun are involved, so: boxes ticked! An amateur pugilist who Jean-Luc collaborated with previously, before the guy joined the army and was stationed in Algeria, is recruited to star in it. So is a professional actress with a pixie cut from Hollywood, USA, via Iowa, who worked with Godard’s beloved Otto Preminger. Production will be casual, to say the least. Spontaneity delivered 24 frames per second will be prioritized over preparation and motivation. The result will change movies forever.

Richard Linklater‘s Nouvelle Vague time-travels to the moment right before modern cinema’s big bang, when the French New Wave crested and Godard’s Breathless would change everything. Tackling the making of a bona fide masterpiece would be enough to keep the Boyhood director busy, but he’s decided to up the degree of difficulty in the name of fidelity. This isn’t just shot in black-and-white, thus resembling the 1960 meta-commentary on American crime thrillers and pulp fictions in all its monochromatic glory. That’s simply a Tribute 101 move. Linklater also insisted the dialogue be in French, a language he doesn’t speak. He throws in retro touches like analog pops and the “cigarette burns” that used to signal reel changes. More importantly, this origin story of a movie and a movement apes the joie de moviemaking and the jazzy looseness of the original to an absolutely amazing degree, replicating an off-the-cuff feeling that’s more than a second-hand buzz. It’s the most blissful time spent in the dark you can imagine. (This hits select theaters today before dropping on Netflix on November 14th, and if ever a valentine was designed to be seen in the company of other film lovers, it’s this one.)

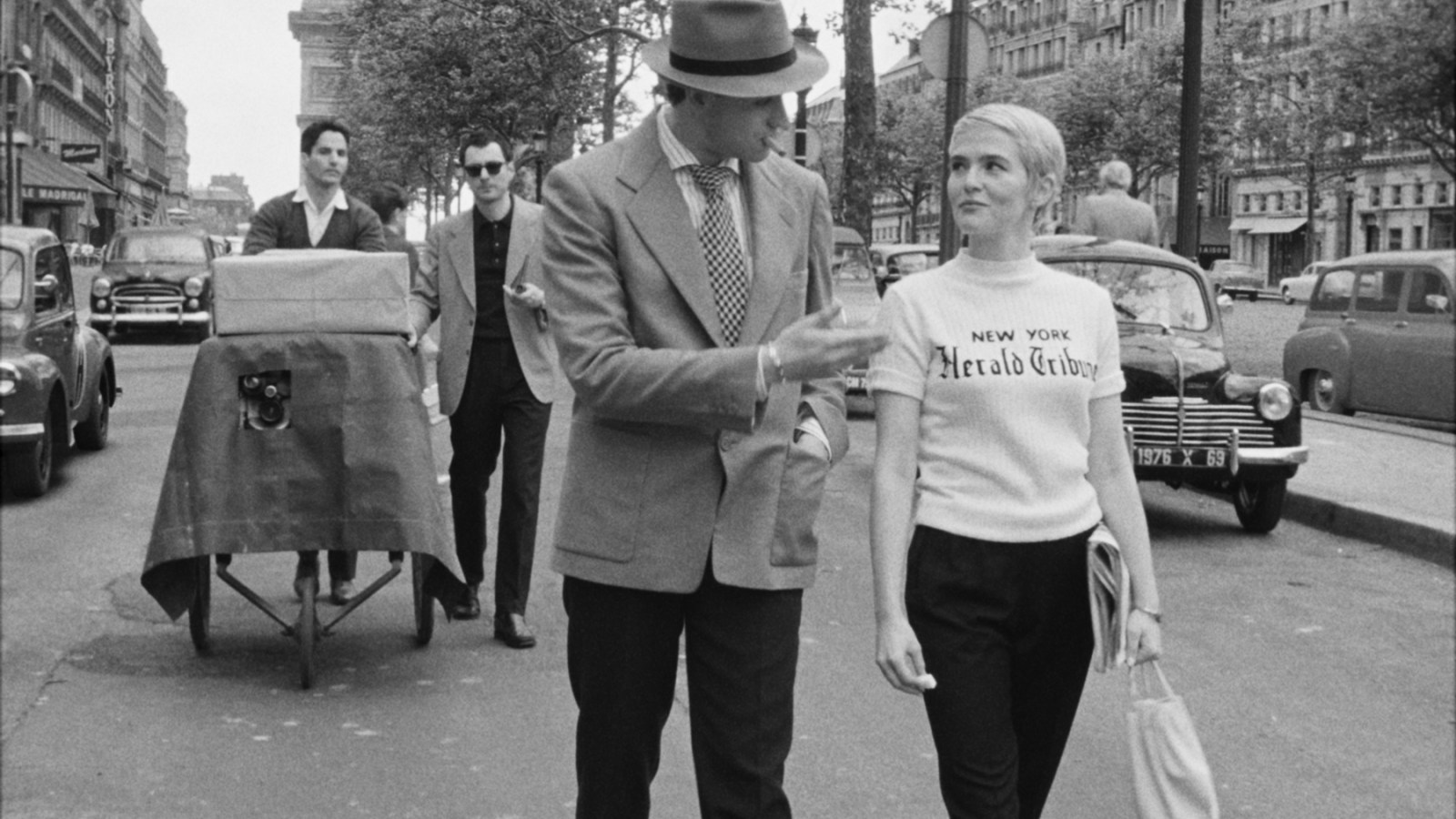

So yes, slip on your Ray-Bans and light up your Parisiennes and ride shotgun with Jean-Luc (Guillaume Marbeck), as he slouches towards Bethlehem, a.k.a. the Cinémathèque Française, and bops around town with Truffaut (Adrien Royaurd), Chabrol (Antoine Besson), and Suzanne Schiffman (Jodi Ruth-Forest). Eavesdrop on conversations with Rohmer and Jacques Rivette in the Cahiers office, the clack of dueling typewriters soundtracking the camaraderie, and play voyeur as everyone’s hero Roberto Rosselini stops by to address the troops and pocket finger sandwiches on the way out. Witness Godard, oozing Gallic charm and hipster cool, convince Jean-Paul Belmondo (Aubry Dullin) and Jean Seberg (Zoey Deutch) and cameraman Raoul Coutard (Matthieu Penchinat) to be down for the cause. And laugh the laugh of the long-converted as this upstart drives everyone from his starlet to producer Georges de Beauregard (Bruno Dreyfürst) and assistant director Pierre Rissent (Benjamin Clery) cuckoo by his unconventional methods and lack of concern over time, money, plot, etc., secure in the knowledge that Breathless will outlast any such petty concerns.

Guillaume Marbeck in ‘Nouvelle Vague.’

Netflix

Other than Deutch, who the filmmaker recruited for his 2016 comedy Everybody Wants Some!!, everyone in the movie is a virtual unknown — though Marbeck will likely get a level-up the same way that Matthew McConaughey, Glen Powell and Jack Black did when they worked with Linklater. But for those with more than a passing familiarity of the French New Wave, the role calls of the key players is a pure rush. The movie introduces them and their mentors-slash-idols like Robert Bresson and Jean-Pierre Melville and Jean Cocteau with identifying disclaimers and portraits that have the actors portraying staring directly into the camera, as if it was fanning out a deck of MVP trading cards. For a certain sect of film nerds, this inspires the same feeling that comic-book readers got when the MCU finally gathered all of its main and deep-cut characters at the climax of Endgame — this is our interconnected universe and these are our superheroes. Cinemavengers, assemble!

Yet you don’t need to have multiple Letterboxd accounts or have argued over which Rivette film ranks as his best (it’s clearly Celine and Julie Go Boating, why would anyone even have this debate at all?!) to appreciate, enjoy and swoon over the spell that Nouvelle Vague casts. Linklater has made a variety of different types of films, from broad comedies (School of Rock) to biopics (Blue Moon) to animated sci-fi (A Scanner Darkly). The Texas native even has a Western (The Newton Boys) on his resume. His specialty, however, is the hangout movie, and with this look back at Godard & co., he’s turned a pivotal moment in film history into a magnum opus of hanging out. “Filming should only be done in a state of urgency and necessity,” an elder statesman lectures. Yet so much of Marbeck’s turn as the newbie auteur du jour exudes a strong vibe that’s best described as “kickin’ back, no big deal,” down to the signature shoulder-slumped posture and louche way he plays pinball. These fanatics may die on many hills in terms of defending B movie directors, or declare that narrative is a bourgeois concept, or stick to their guns in terms of an editing style that reflects the film’s “impatience.” But they also enjoy each other’s company, and dear God(ard), so do you.

“The best way to criticize a film is to make one,” our hero notes, after seeing something that he declares a piece of shit. The best way to show your love for a work of art is to make a testament to its creation, even if such endeavors don’t always hit bullseyes with every shot. The enfant terrible of the French New Wave walked so Linklater and his ilk could run, and you can tell how much fun the now-veteran American filmmaker is having resurrecting not only the late, great Jean-Luc’s puckishness but the anything-goes dynamic of his own beginnings. Godard’s ode to American movies that required only a girl and a gun begat freak-flag-flying films like Slacker, which begat Linklater’s career, characterized by him following his own muse. Nouvelle Vague is as much a testament to being young, idealistic and a cinephile — full of opinions, drunk on your own taste, and madly in love with the movies — as it is a making-of recounting. The Austin-based director sees not just a figurehead to emulate in the artist in late 1950s Paris but a reflection of a kindred spirit. Game recognizes game.

Leave a Reply