Colossal Biosciences — which announced in April that it had brought dire wolves back from extinction (only to be met with a howl of critics who called the claims overstated) — is teaming up with filmmaker Peter Jackson on a new animal revival project.

The company announced Tuesday that it is working with Jackson and New Zealand’s Ngāi Tahu Research Centre to bring back the moa, native flightless birds that went extinct around 600 years ago. Found nowhere else on Earth, moas comprised nine species — with the largest, the South Island Giant Moa, clocking in at around 400 pounds with a height of up to 12 feet when its neck was outstretched. That made it likely the tallest ever bird ever to have existed.

“I would hope eventually we can bring back all nine species of moa to really see and understand them and study them,” Jackson tells The Hollywood Reporter, adding that the collaborators hope to bring back the South Island Giant Moa first. It, along with other moas, went extinct around 150 years after Polynesians settled in New Zealand.

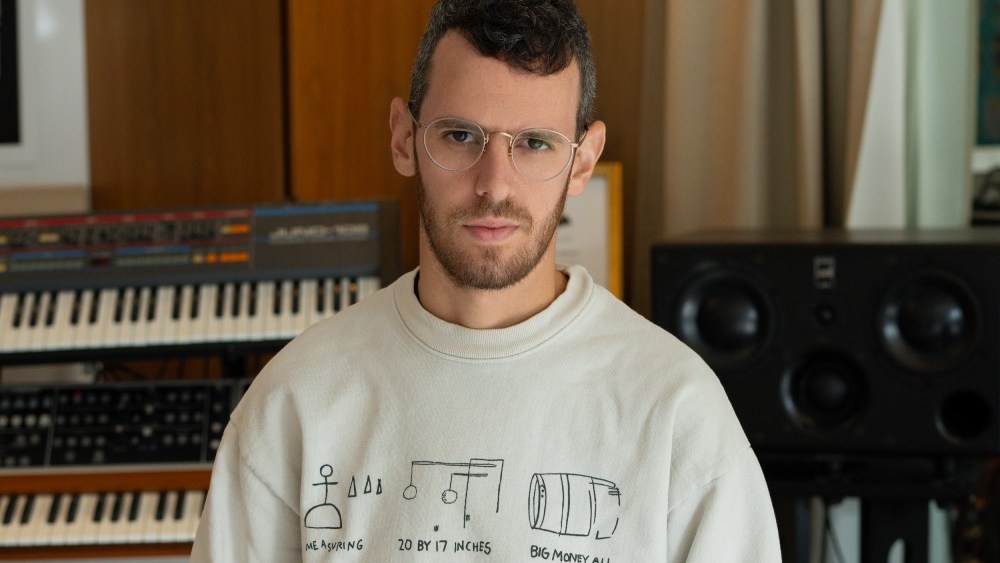

“When you grow up in New Zealand, you grow up knowing about the moa. It’s just something that’s in our DNA,” continues Jackson, who, along with his partner Fran Walsh, invested $10 million in Colossal Biosciences last year.

Long fascinated by the moa, Jackson and Walsh have been collecting bones of the extinct bird for years. “We’ve collected about 400 moa bones,” says Jackson, explaining that they urged Colossal to add the moa to the list of species the company plans to resurrect from extinction. (The company has previously detailed plans to bring back the Tasmanian tiger, the woolly mammoth and the dodo.)

“When we had our first Zoom call with Colossal a couple of years ago, the moa wasn’t on their list on their website. We said to them, ‘Are you interested in the moa? And [Colossal co-founder] Ben [Lamm] said, ‘Yeah, we sure are. So we made a condition of our investment that all of our dollars go into the moa project.” As part of the agreement, Jackson and Walsh are giving Colossal the use of their collection of moa bones for research. “So we were able to not just invest in Colossal, but also bring our bones to the table, as it were,” continues Jackson, whose upcoming projects include producing Lord of the Rings: The Hunt for Gollum, set for release in 2027. “And they’ve been sampled for DNA. We were very pleased about that.”

In its request to bring back extinct animals, Colossal Biosciences uses a combination of genome mapping — using still-extant tissue and bones — and pioneering genetic engineering. The animals are not directly cloned from decades- or centuries-old tissue. Instead, a living, closely related species is genetically edited to produce the closest scientifically possible match of the extinct species. In the case of Colossal’s trumpeted dire wolves, the animals were created by developing the most complete genetic map ever made of the extinct species and then making 20 genetic edits of the genetic code of a near-cousin, the grey wolf, selecting for specific dire wolf characteristics. Some scientists have criticized Colossal’s dire wolf claims as “misleading,” saying that it’s an exaggeration to say that the species has altogether been brought back from extinction.

To resurrect the moa — which was the subject of a 1973 DC Action Comics book in which it fought Superman — Colossal will need to work with the genetic code of the closely related tinamou bird, which is native to the Americas. Colossal Biosciences has already begun building reference genomes of the tinamou as well as of the emu, Australia’s species of large flightless bird. “We started in October on this project,” says Lamm. “In the next year, the project is really about sequencing bones and getting more and more [moa] samples and the research so we know what are the edits that need to be made.”

The moa project is a partnership between the Ngāi Tahu Research Centre, Colossal and Jackson. The research center — which will take the lead in directing the moa efforts — was established in 2011 to support the Ngāi Tahu, the principal iwi (Māori tribe) of the southern region of New Zealand. In contrast to its work with other animals, explains Lamm, “we’ve taken a different approach [with the moa] where we are almost like a support function to the Māori.” Colossal believes the partnership “signals a new era of indigenous leadership in scientific innovation.”

Kyle Davis, a Ngāi Tahu archaeologist who is working with Colossal and Jackson, explains the importance of the extinct bird to Māori culture. “This animal features in our oral histories. It’s iconic and what we call a taonga, a treasured entity from the past. It’s hugely significant to us,” says Davis, adding that “Peter [Jackson] is, through the cinematic medium, a world builder. And Colossal is a world preserver and restorer. So for them to accept the invitation to share our tribal dream of ecological restoration and adding de-extinction to that milieu is just an absolute honor and privilege.”

If the partnership is successful, it’s likely that the birds will live in an ecological preserve in New Zealand. “The concept isn’t to release the giant moa into the wild. That’s certainly not the initial goal,” says Jackson. “New Zealand’s a very different country now to how it was 600 years ago. There’s roads, there’s cars, there’s cities, there’s so many more people. It’s not necessarily a good idea to just release it into the wild. That may happen, but it would happen, I think, decades down the track. It would have to happen after a lot of studying, a lot of thinking.”

Adds Lamm, “Going back to the spirit of the partnership, it’s really up to the Ngāi Tahu. It’s really up to what they want. We look at ourselves as supporters of their vision.”

Lamm, calling the moa project a “redemption story,” hopes that the efforts will inspire interest in ecology and biodiversity and drive ecotourism to New Zealand. As part of its commitment, Colossal Biosciences will also invest funds in helping preserve other species in New Zealand which are currently threatened with extinction or loss of abundance. “Saving and protecting what’s there — at the direction of the Ngāi Tahu Research Centre — is something that’s critical to the project,” says Lamm.

Leave a Reply