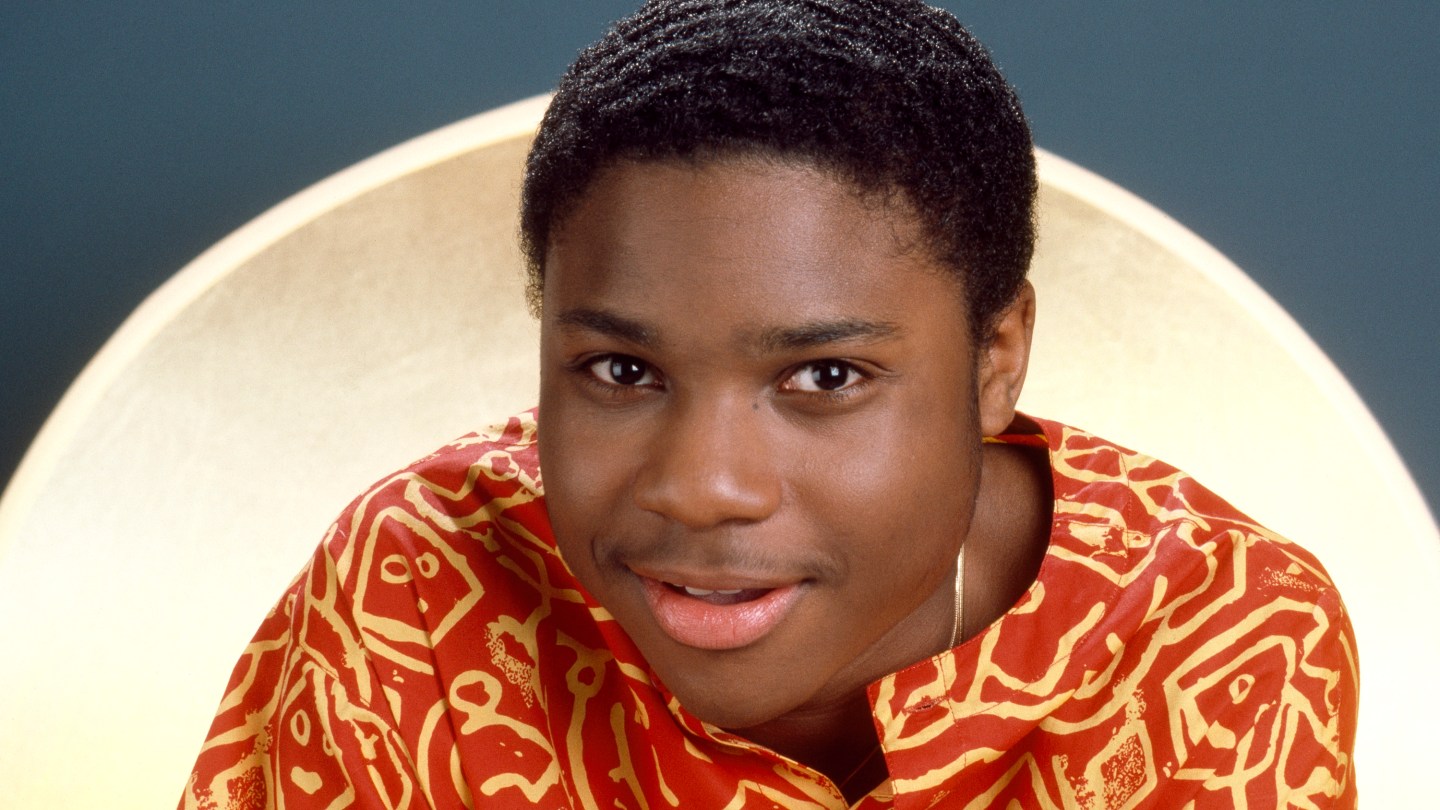

As a kid, you didn’t need to have smoked marijuana or even know what it was (I plead ignorance on both counts — really, Mom!) to vibe with a flustered Theo Huxtable after his suddenly unsmiling parents found him with a joint in his library book in a 1985 episode of The Cosby Show.

Such a tableau would confound today’s generation of young well-meaning miscreants, in part because they smelled pot smoke three times already just walking to the store and also, what’s a library book?

But Theo meant everything to a whole generation of kids who saw in him the idea, as Questlove put it so eloquently upon the news of Malcom-Jamal Warner’s death on Monday, of “what does it mean to be an adult without depending on your parents?”

Warner’s death at 54 in a drowning accident hit hard. And it’s not just him. For anyone considered a part of Gen X — roughly, those of us who were kids at some point from the mid-‘70s through the end of the ‘80s — this is now the third year in a row we’ve lost someone pretty much indispensable to our youth. First Matthew Perry in 2023, then Shannen Doherty in 2024 (a double whammy with Our House and 90210, and especially painful just a few years after Luke Perry) and now Warner. All were born within 20 months of each other beginning in mid-1969. Which is to say, too close to any of us.

And, yes, I know Perry also was a millennial favorite since Friends came on in 1994, but he was Gen X himself, and also, are we really going to shade Second Chance like that?

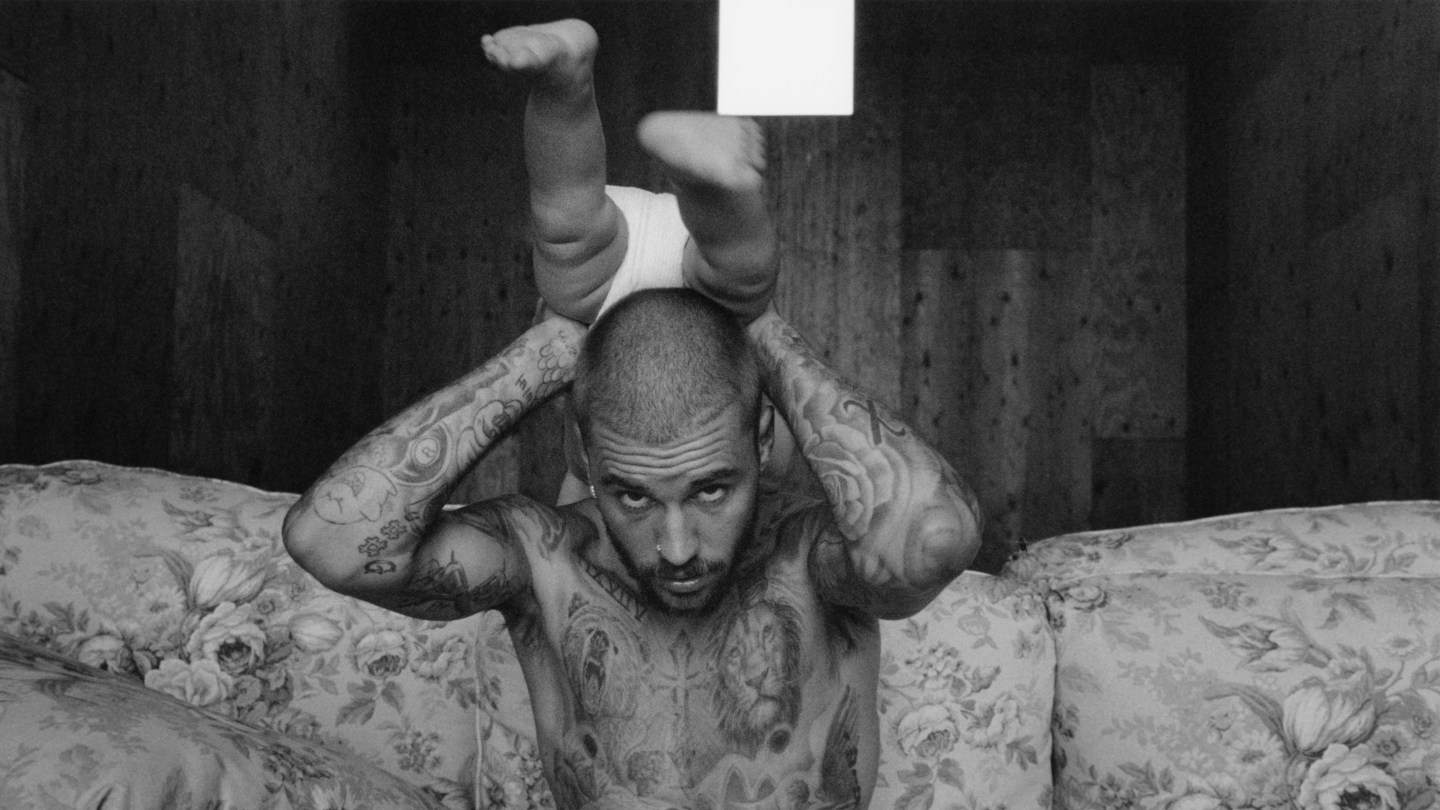

’80s-era Ozzy.

And then Tuesday, Ozzy Osbourne, who of course transcends generations with all his early 2000s second-life reality-show MTV popularity but who was inextricably tied to Gen X, first with the crazy 1980s schoolyard stories (the original internet) about a PETA-unfriendly activity at his concert (actually an accident), and then with his music. If you didn’t blast “Mama, I’m Coming Home” out your dorm window on the last day of classes in the ‘90s, could you really be said to have gone to college at all?

Ozzy was the embodiment of early MTV. And now he’s gone. Along with, of course, MTV itself.

The stuff we thought would be here forever has left before its time. Theo was teenage possibility; MTV was the cutting-edge incarnate. It was all supposed to tell us what was coming. Not remind us of what is gone.

Ozzy at least reached a relatively ripe age of 76. But Gen X has lost too many of its childhood musical heroes far too young, Prince and Tom Petty and Whitney Houston and Michael Jackson and George Michael. They would have filled the best cassette mix tape that one summer in camp, where if someone from the future showed up to say they’d all be gone before most of us left our 40s (and, outside of Petty, before any of them got out of their 50s) we would have shooed them from the basketball court and just cranked up the boom box louder.

These deaths and the sense of dread they bring are on the one hand a surprise. But also, maybe not? Gen X was long defined as the first postwar generation to think we would do financially worse than our parents; bleakness is hardwired into us from our formative years. We were the first to experience parental divorce on a mass scale, the first to be exposed to the idea that the people who grabbed Etan Patz and Adam Walsh could well grab us, the first to see 20th century techno-optimism go up in a fiery cloud of space-shuttle smoke — the first, maybe, to be told the world was garbage, and that’s if you live through it.

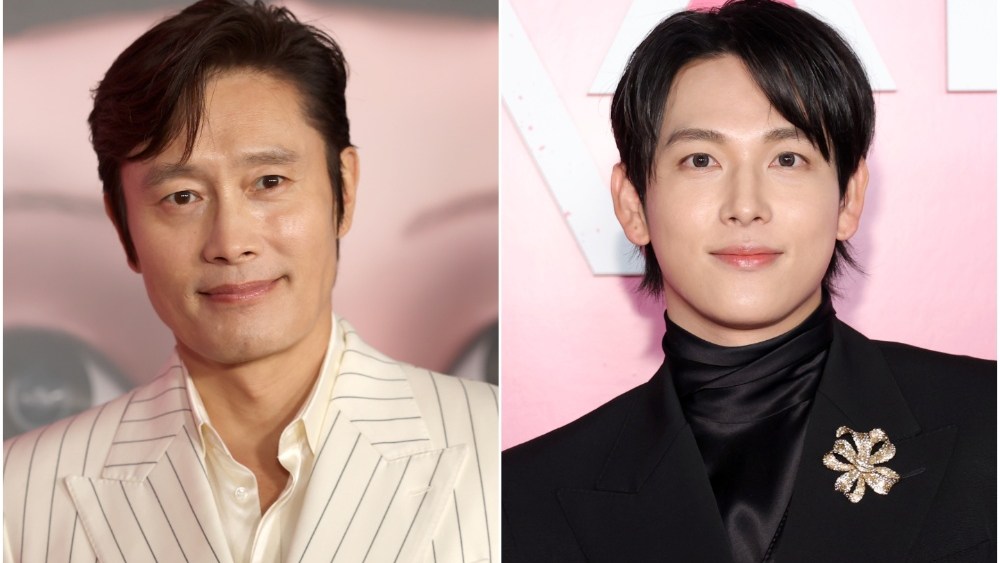

Kurt Cobain in 1990.

The defining moment of being a Gen Xer, after all, was Kurt Cobain’s suicide in 1994. I know people say the generational divide is the internet or cellphones or being an adult on 9/11, but I think it will always be Cobain. If you are old enough to remember what happened and how you felt that April day he took his life, you’re a Gen Xer. If you’re not, you’re not. And how we felt was, everything sucked, everything will always suck and the one guy who was clear-eyed enough to point out how it sucks was so overwhelmed by said suckitude that he couldn’t go on anymore. A kind of generational irony grew out of that realization. But it was cultivated in a greenhouse of despair.

I know all the actuarial stats that Gen X celebrities are not really dying at a faster rate than boomer celebrities did, that there is no greater percentage of them passing in their 50s than there was in a previous generation (though there were, thanks to the proliferation of cable and media in the ’80s and ’90s, more broad Gen X celebrities, period, which does increase the number).

But it is a feeling — that a generation marked by loss is now dealing with it, again and again, watching a childhood that seems gauzier with each passing day also get more painful and lost with each passing day. Perhaps too many early years of watching Friday the 13th and Nightmare on Elm Street movies, with its heroes getting picked off one by one, has epigenetically messed with our brains and infused a feeling of grim inevitability. But after learning of Theo Huxtable’s death, a lot of us turned to each other or just to ourselves and darkly asked, “OK, so who’s next?”

I don’t know how we shake this feeling, except maybe by getting a new Gen X hero. A president, I always thought, might help. But the way things are going, we’ll just skip from boomers right down to millennials and there will never be a Gen X president. I’d like to think I’m wrong. But I’m too much of a Gen Xer to be that optimistic.

Trevor Horn of The Buggles in a scene from first video to be shown on MTV in 1981.

Leave a Reply