When he was a 19-year-old working any gig he could scrounge up around Boston, Sean O’Brien found himself driving on the set of Malice, the 1993 thriller starring Alec Baldwin and Nicole Kidman. A fourth-generation Teamster from Medford, O’Brien wasn’t the type to sip white wine and nibble appetizers with big-time movie stars. But he struck up a relationship with Tom Cruise — then married to Kidman — who often was lingering on the sidelines on shooting days.

“I was the youngest guy on the set,” O’Brien recalls, “and he was always coming up talking to me.” The two became so friendly that they even got a touch football game going with Baldwin and a group of Teamsters on an off day.

The moment tells of more than just Cruise’s working-man conviviality. It opens a window into the interest in entertainment industry relationships held by International Brotherhood of Teamsters general president O’Brien, who now seeks to bask in a Hollywood presence and further its priorities in a way that goes well beyond a weekend sandlot scrimmage. These days, following his controversial decision to speak at last summer’s Republican National Convention, the 50-something union boss has become one of very few industry emissaries with real clout in the Trump White House, an awkward alignment that’s stirred consternation among Hollywood’s liberal establishment.

Though industry outsiders might associate the Teamsters more with 18-wheelers than star trailers, the organization’s members are an inescapable presence on film and TV sets. With Hollywood roots going back to the Great Depression, its 15,000 entertainment worker members of course drive (hauling everything from set dec to talent); cast those very stars to begin with (some 700 of Hollywood’s casting directors are represented by the Teamsters); scout production locations; train set animals; and feed cast and crew.

A brash blue-collar personality who can seem to enjoy provoking more effete Hollywood types — O’Brien has appeared on his podcast in a black veterans-group T-shirt that reveals his bicep tattoo as he tells saltily colorful stories about his Boston union days — the labor leader believes he can change the standing of the entertainment business in D.C. and, as a result, help ensure the survival of the industry. He is lobbying hard for a federal tax credit, has come out in support of Trump’s 100 percent tariff on overseas productions and wants Apple and Amazon to be “put in check” for the harm he believes they’re wreaking on the industry. But the contract is far from signed on whether the negotiator is the bridge to Washington that the industry has been waiting for, or an attention seeker more interested in viral video clips of himself than a healthier Hollywood.

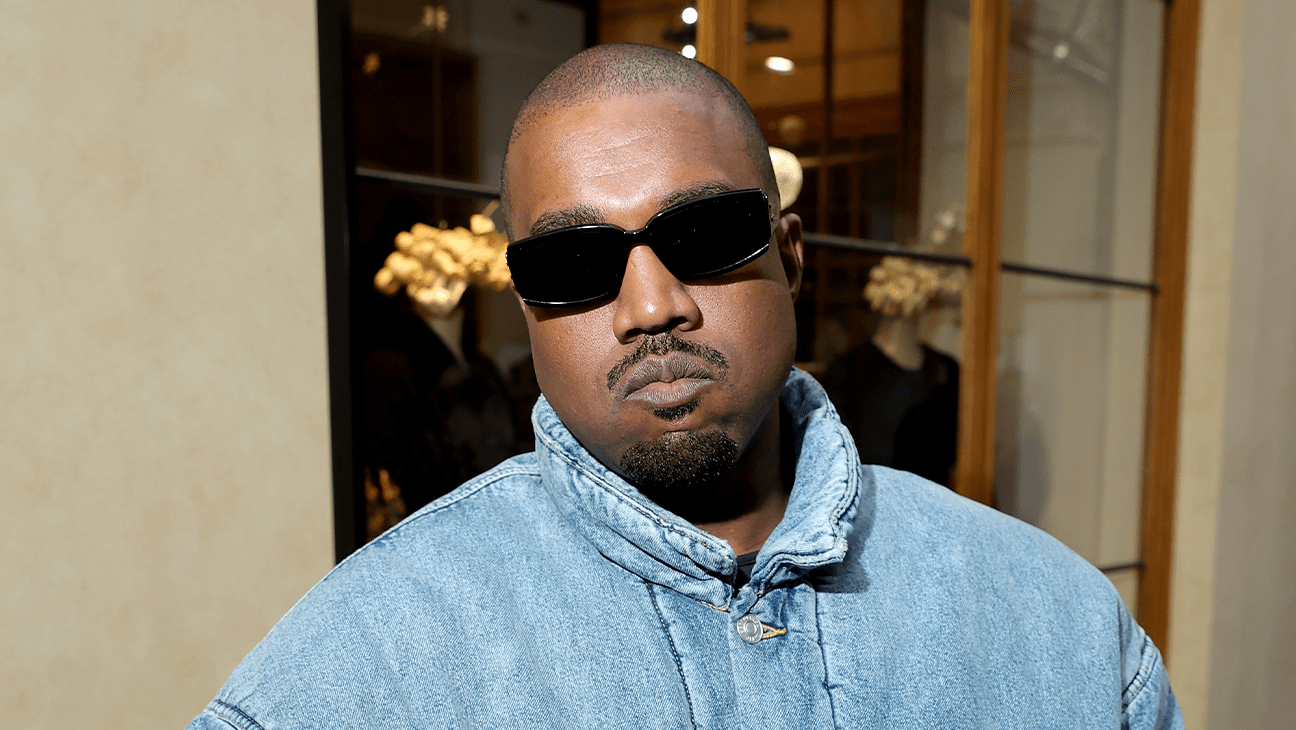

Mark Peterson/Redux

O’Brien’s story isn’t just about the emergence of a blue-collar power broker of showbiz policy — it’s a tale of the braided knot between the gritty world of the Boston white working class and an entertainment business 3,000 miles away that just can’t stop portraying it. At times, O’Brien can seem like a character in the latest Ben Affleck or Mark Wahlberg movie rather than a savvy political insider who happens to be a pal of both of them.

His public persona merges an old-school toughness with a new-age media savvy — sometimes simultaneously. A few years ago, one of the most surreal sights the modern Congress has ever witnessed had O’Brien at its center when Oklahoma Republican Sen. Markwayne Mullin challenged him to a fistfight during a hearing on unions’ impact on working families — a challenge the labor leader seemed eager to accept until Sen. Bernie Sanders stepped in to (slightly) lower the temperature. The video went viral, and millions of people who’d never heard of Sean O’Brien suddenly knew his name.

As he has staked out his turf, O’Brien has created something unique in the modern era of Republican and certainly Trumpian politics: a figure who can front Hollywood interests from right inside the White House. But a simple question remains unanswered: Does Hollywood actually want him there?

The floor of the Republican National Convention was abuzz. Sean O’Brien, the leader of one of the largest and arguably one of the most powerful labor unions in the land, had just broken with tradition and spoken at the GOP gathering. That had never happened before. Usually labor leaders turned up at the Democratic National Convention, which, possibly as a result of the RNC speech, O’Brien then wasn’t invited to attend.

The speech was a reversal for more than a union. O’Brien himself had dissed Trump during his own election campaign to lead the union, praising then-President Joe Biden and a Democratic-led Congress in 2021 for the COVID stimulus bill that bailed out a Teamster pension fund for nearly 400,000 members. The bill faced strong opposition on the Hill. Vice President Kamala Harris broke a Senate tie to advance it.

“I want to commend everybody who worked hard on that,” O’Brien said at an election debate against his opponent, Steve Vairma, adding, “You know, it’s unfortunate that a lot of our members voted for Trump.” (He also once described the National Labor Relations Board under Trump’s first term as a “four-year reign of terror.”)

Such comments made O’Brien’s about-face in Milwaukee — he gave Trump the ultimate Teamster compliment by calling him “one tough SOB” — that much more striking.

Pundits contorted themselves to figure out O’Brien’s game. “Was he surreptitiously sticking it to the party of Big Business?” wondered The New York Times politics writer Jonathan Weisman. But a more straightforward explanation might have also applied: O’Brien was manifesting a move to working-class populism that was rippling through parts of the Republican coalition (a point that O’Brien would later bear out by aligning with Missouri Republican Sen. Josh Hawley, who has positioned himself accordingly). An internal poll conducted by the Teamsters ahead of the 2024 election found about 60 percent of members supporting Trump, O’Brien says.

But the leader says one of the biggest reasons to swing to Trump is simple realpolitik. “We have never had access like this,” says O’Brien, who also visited Mar-a-Lago shortly before the inauguration but says he’s still a Democrat. Now he talks with the president, he says, two to three times a month, far more than he ever talked to Biden. “Most of it’s about what’s going on,” O’Brien says of the conversations. “He’s very sympathetic to our relationship and the relationship with working people.”

Yet O’Brien is vague on what, exactly, all those phone commiserations have yielded. Asked for examples, he first notes the appointment of Lori Chavez-DeRemer as Labor secretary. The naming of the union-leaning former Oregon congresswoman to the post — seen in D.C. as a kind of return-the-favor for O’Brien’s decision not to endorse Harris in front of his 1.3 million members — is no small thing given how many departments under Trump, from education to the environment, seem to be undermining their agency’s very goals (though progressive stalwart The Nation has strongly criticized Chavez-DeRemer as anti-union). O’Brien is vague in describing other achievements, saying in an interview only that “we have been consulted with on many issues from the administration” and that “we’ve got full access and we’ve got credibility.”

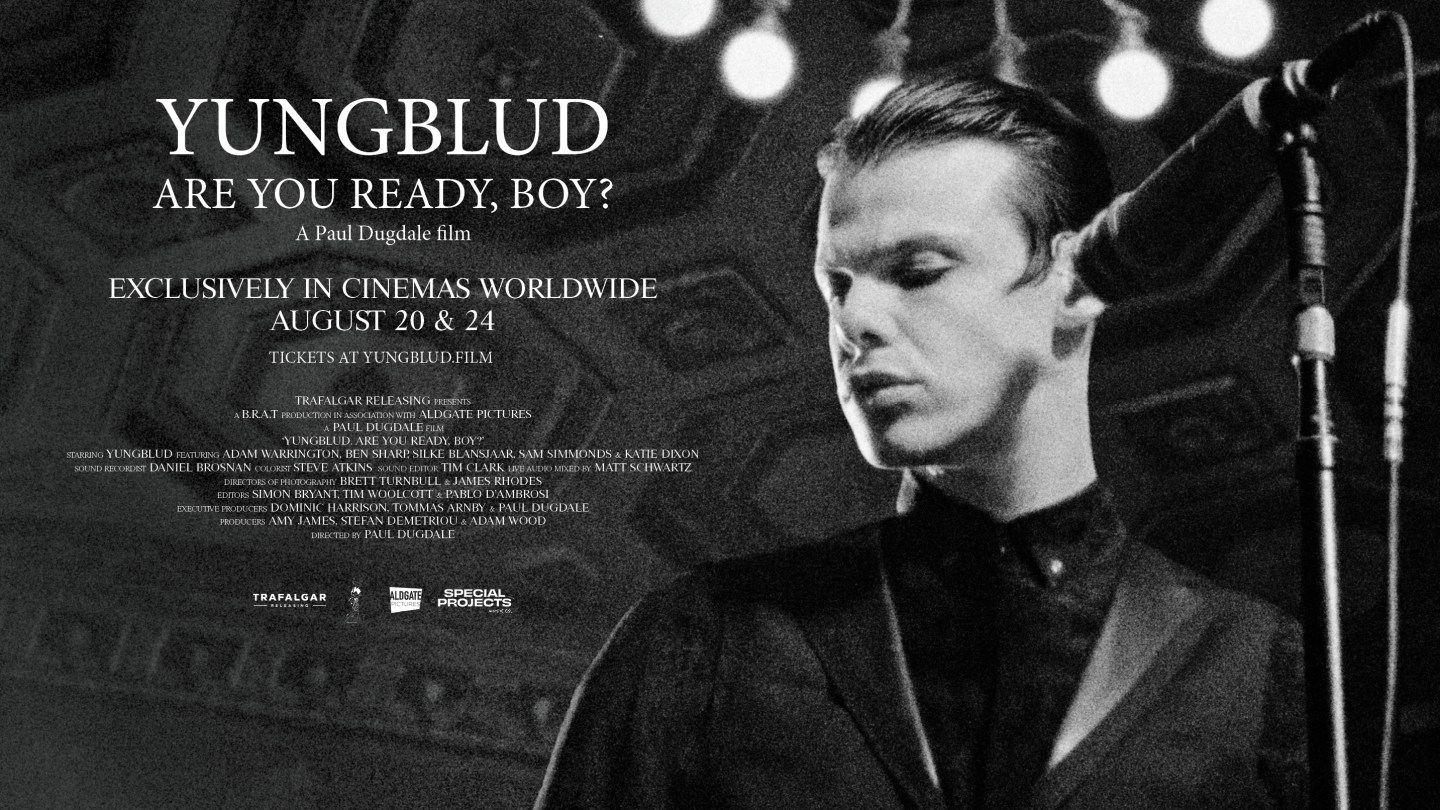

O’Brien listens as his ally, Hollywood Teamsters leader Lindsay Dougherty, speaks on the picket line during the 2023 writers and actors strikes.

Chris Delmas/AFP/Getty Images

Such acceptance hasn’t sat well with segments of the Teamsters’ leadership. Richard Hooker Jr., secretary-treasurer of Local 623 in Philadelphia, believes the White House coziness has mortally damaged both the Teamsters’ standing and its goals.

“We are the laughingstock of the labor movement with the general president’s flirtation with Trump,” Hooker tells THR. “When you are a labor leader, it’s supposed to be, an injury to one is an injury to all. So when [nearly] 50,000 TSA workers lose their right to collectively bargain, and the strongest arm of the labor movement doesn’t say anything, that sends a loud message to the employers that they can do whatever they want,” he adds, referring to O’Brien’s silence in response to the administration’s decision in March to neuter workers’ rights at the Homeland Security agency.

Instead of putting the White House on speed dial, Hooker says, the Teamsters “should be in the mud with everybody else fighting tooth and nail against Trump and his regime.” The Philadelphian is running against O’Brien in next year’s union elections.

To some critics, O’Brien’s alignment with Trump goes beyond utilitarian benefit to a place of identifying with brawler white-male politics; like the president, O’Brien regards himself as a sharp negotiator and, more troublingly to many, has offered up anti-immigrant rhetoric. (“I think the biggest problem is people are trying to protect illegal aliens that come over here and commit crimes, and that’s unacceptable,” he told Hawley on his podcast.)

“Under the cover of being bipartisan, what Sean O’Brien has done is use the shortcomings of the Democrats to cozy up to the far right,” Joe Allen, a left-wing author and former Teamster who has been critical of O’Brien on the progressive site Counterpunch, tells THR. “To me, that’s about his own politics. But whatever you believe, I don’t think you can argue any of this is good for labor,” Allen says, noting that Trump has “a non-functioning NLRB, a non-functioning OSHA and ICE going after working people trying to raise a family.”

Those critics may or may not prove to be a thorn in O’Brien’s side. Even those who don’t like O’Brien say he’s a master politician, an instinctual learner who has no formal background in politics — he left the University of Massachusetts at Boston after one term to join his father’s union as a heavy-equipment driver — but has learned how to strategically corral those once disdainful of him, as he did with left-of-center faction Teamsters for a Democratic Union before his 2021 election. O’Brien handily won that race (he ran on a reform platform promising tougher negotiations with UPS) even though his opponent had been handpicked by the incumbent, James P. Hoffa, generally a golden ticket. The upset surprised some members and observers. Once considered a watchdog for the excesses of union leadership, the Teamsters for a Democratic Union mostly now follows O’Brien.

Even casual users of social media might be struck by how often O’Brien seems to be meeting with Republican leaders on entertainment industry issues lately, then posing for a photograph to document his encounters. There goes the union boss talking to Texas Gov. Greg Abbott about film tax credits in the Lone Star State; here he is at the FCC with chair Brendan Carr gabbing about the Paramount-Skydance merger.

O’Brien says he and Trump speak frequently about entertainment issues. Recently, the union boss has been bending the president’s ear on the issue of the federal tax credit and overseas production tariffs. The Teamsters enthusiastically supported Trump’s latter plan, which has seemingly fallen by the wayside since the president announced it in May.

“We thank President Trump for boldly supporting good union jobs when others have turned their heads. This is a strong step toward finally reining in the studios’ un-American addiction to outsourcing our members’ work,” O’Brien and the head of the Teamsters’ motion picture division, Lindsay Dougherty, said in a statement after the provocative May post on Truth Social. Other Hollywood labor guilds were more muted.

O’Brien even went on Fox News to endorse the plan to the network’s many Trump fans, giving it an air of Hollywood rank-and-file legitimacy. “Tariff them, make them work in the United States and take a little bit less off your bottom line,” he said.

O’Brien says his affinity for Hollywood came early. His late father, Billy O’Brien, was a transportation coordinator with Boston’s Local 25 for more than five decades. He would sit in their home and flip through the trades to see where his next gig was coming from, often landing big ones, such as on Clint Eastwood’s 2003 opus Mystic River or the quintessential Boston movie Good Will Hunting. His fascination with a kind of cinematic toughness was honed early in life, too. O’Brien, now the father of two sons, loved the 1990 gangster movies Goodfellas and State of Grace and continues to watch them to this day (he has seen the former “thousands of times” and the latter “a hundred times”).

The labor leader’s fears for Hollywood are similar to what a lot of people in town quietly grumble about: a tech takeover. While studio bosses have historically been the enemy of organized labor, O’Brien sounds an almost wistful note in talking about their stewardship of a tradition he thinks Silicon Valley is now ruining.

“They need to be put in check, not look to destroy an industry full of the most creative people for hundreds of years,” he tells THR of tech entertainment giants. “The United States of Amazon, they are only in the streaming industry because it’s a marketing tool. What is their biggest business? Their biggest business is their cloud and Amazon Prime.”

On that point, Hollywood labor leaders would likely not disagree. But they might note that Amazon and Apple also provide plenty of industry jobs. In a way, O’Brien is channeling the concern that even in 2025 can remain unusually unaired in industry circles: If entertainment is not these companies’ core business, what happens when they get tired of the side hustle?

The Teamsters leader also is worried about AI and has become an ally of anti-AI advocate Justine Bateman, who sings his praises and even recruited the Teamsters to sponsor her “No AI” film festival in Hollywood in March.

“The AI threat, it’s not looming. It’s a clear and present danger,” O’Brien says. “You look at the appetite for convenience in society [not] realizing what the consequences are.” Driverless trucks are of course a bête noire, but O’Brien says he wants to be fighting equally hard against the tech on studio lots.

“I mean, you can make a movie on an iPad and create Hollywood characters,” he says. “We’ve just got to be vigilant on making sure there’s protections against AI and utilize AI where it’s necessary and, where it’s not necessary, mandate that it can’t be used.”

But Trump, who has signaled little interest so far in AI regulation — he gutted a Biden executive order that had modestly attempted that — is an unlikely ally in this regard. And it remains perplexing both inside and outside Hollywood how O’Brien’s interest in human-centric labor squares with Trump’s seeming apathy on the subject.

Other Hollywood-affiliated unions are conspicuously chilly to Trump (SAG-AFTRA has barred the former Apprentice star from readmission, and IATSE has decried him for allegedly crossing its picket line). In response to requests for comment from major Hollywood unions about O’Brien’s efforts with the White House, only the actors’ union responded, with leader Duncan Crabtree-Ireland not mentioning Trump but praising the Teamsters as a “powerful labor ally” whose solidarity “helped maintain momentum” during its recent strike. The union added that O’Brien himself walked the picket lines and “inspired SAG-AFTRA members.”

Still, there’s a sense that some are desperate enough in a contracting production business to turn to Trump for help, even if they have to hold their noses. “We do have support from those other unions,” O’Brien says. “They’re just not as vocal.”

The Bostoner’s uneasy relationship with the entertainment labor community over the Trump factor was exemplified by an episode of his podcast Better Bad Ideas released in March with comedian Adam Conover, who is a board member of the WGA West. As O’Brien wound down the congenial conversation, Conover buttonholed the host on White House actions that have alarmed labor leaders, such as federal layoffs, the shuttering of DEI programs and the firing of an NLRB board member. “I think we’ve got to be clear-eyed about when people in power currently are actively trying to make it harder for us to organize,” Conover confronted O’Brien.

“People are going to blow things up and hopefully rebuild them,” O’Brien offered, and somewhat jarringly changed the subject to job losses caused by Biden actions on the Keystone Pipeline.

Domestic productions offer O’Brien an opportunity to help Hollywood, particularly with the federal tax incentive that the industry hopes to convince Washington Republicans to support. Still, the jury is out on whether O’Brien or anyone else can persuade Trump to offer a perceived gift to an industry he wars with, based in a state whose governor he can’t stand. (Some Hollywood labor figures have been privately skeptical that the shuttle diplomacy by either O’Brien or Trump pal and “special ambassador” Jon Voight will amount to much. But one insider maintains O’Brien’s presidential access has, at least, been effective in keeping Hollywood issues top of mind with an easily distractible president.)

O’Brien contends Trump is a new man. “When you’re running on a platform of wanting to be the party or the president for working people, of course you’re going to change your platform,” he says of the president. “I think he’s got a lot better people around him making decisions.” O’Brien says that if the administration made what he felt were anti-labor moves, “obviously [we’d] hold them accountable,” even as his organization appears to have been largely silent on many issues that have alarmed other advocates.

O’Brien says his critics might be confused because of the novelty of his approach. “We’re doing something different that nobody else has done,” he says of the Trump relationship.

A cozy or at least transactional relationship between a Teamsters boss and a controversial Republican president is actually not new. In the 1970s Jimmy Hoffa ally Frank Fitzsimmons had a strong in with Richard Nixon, which resulted in some benefits to the Teamsters on his watch. And IBT boss Jackie Presser helped Ronald Reagan get elected in 1980, leading to a place on Reagan’s transition team. Teamsters have simply tended to avoid the political lockstep of other labor groups.

“They don’t feel restrained historically,” says David Witwer, an American Studies professor at Penn State Harrisburg and author of Corruption and Reform in the Teamsters Union. “They wouldn’t say, ‘well, we wouldn’t want to do this because our colleagues in other unions aren’t doing this.”

One big question is how the Trump dynamic affects O’Brien’s relationship with motion picture division director Dougherty, who has shown more socially liberal colors than some previous Teamster leaders but also strong loyalty to her boss. She had the union participate in the Los Angeles Pride parade for the first time, added more diversity to her executive board and brought together Teamsters for a Martin Luther King Jr. celebration. The highest-ranking officers on O’Brien’s general executive board are a diverse group, though he did get into hot water when his administration fired 20 people from the Teamsters’ organizing department, the majority people of color, leading to a $2.9 million settlement in a racial discrimination lawsuit, with the Teamsters denying any wrongdoing, The Guardian has reported.

Dougherty, a bold personality disposed to tattoos (including one of the elder Hoffa) and R-rated language (her catchphrase is internet favorite “fuck around and find out”), has proved to be both a strong ally and asset for O’Brien.

A longtime Teamsters staffer and former transportation dispatcher on projects like Transformers: Age of Extinction, Dougherty has raised the profile of the 6,400-member Local 399 in North Hollywood.

O’Brien, who met Dougherty during the 2000s through her father, the secretary-treasurer of a Detroit Teamsters Local, cannily asked her to join his political slate ahead of the union’s 2021 election. He was looking to challenge the handpicked successor to 23-year incumbent James P. Hoffa, Jimmy’s 80-year-old son, in coalition with the Teamsters for a Democratic Union, and as an outspoken millennial, Dougherty helped solidify his branding.

O’Brien with Donald Trump and Secretary of Labor Lori Chavez-DeRemer in 2024.

@teamsterSOB/X

In an interview, Dougherty said she was drawn to joining O’Brien’s 2021 slate because he was “aggressive” and “forceful,” as opposed to a previous leadership that was “complacent.”

O’Brien and Dougherty together have shaken up the Hollywood labor world with increasingly tough talk. O’Brien one-upped Dougherty’s spicy rhetoric when he came to town in advance of Local 399’s contract negotiations in 2024 and repeatedly called the studios a “white-collar crime syndicate.”

The question, of course, is whether all the sound and fury produces anything. Critics say that the 2023 UPS fight didn’t do as much good as O’Brien claimed, preceding a bloody period of tens of thousands of job cuts as automation takes hold amid facility closures. “The process for Sean,” says John Palmer, a vp at large for the Teamsters from San Antonio and prominent O’Brien critic, “is to talk tough and sell short.”

The new UPS contract, ratified by 86 percent of voting members, was praised by some members at the time for raising wages and improving working conditions. “I mean, the UPS agreement speaks for itself,” O’Brien says of the deal.

Before he was whispering in Trump’s ear about Hollywood, O’Brien was cupping his hand to Hollywood. Shortly after he became president of Local 25 in 2006 on a platform of de-criminalizing the chapter, O’Brien flew out from Boston to do a backlot tour and reassure studios that, contrary to (well-earned) perception, Boston was not a scary place to shoot and that the Teamsters didn’t make negotiations difficult for producers. O’Brien’s predecessor George Cashman pled guilty to extortion, following a series of troubling incidents that included a grand jury investigation into shakedowns of producers on reportedly such films as The Cider House Rules and The Perfect Storm. All of it had prompted a 2000s-era Hollywood abandonment of Massachusetts.

O’Brien told Hollywood the union had been cleaned up and the industry wouldn’t face that kind of bullying again. And while tax credits spearheaded by then-Gov. Deval Patrick probably had as much to do with it as anything that O’Brien said, Hollywood soon returned, shooting movies like the Bruce Willis starrer Surrogates, the Mel Gibson vehicle Edge of Darkness and Ben Affleck’s The Town in the late 2000s. Affleck credits O’Brien with a Boston movie renaissance. “I believe Sean is meaningfully responsible for the amount of [Hollywood] work that came into Boston as a result [at the time],” the Oscar winner tells THR, adding that “he personally made sure that our movie company had a good experience.”

But O’Brien’s tenure didn’t always go so smoothly on the Hollywood front. About five years after the Town shoot, a group of Teamsters picketed the Bravo hit Top Chef in an attempt to force the production to sign contracts with the union instead of local drivers and, according to allegations in an eventual trial, hurled misogynistic, homophobic and racist invective at cast, crew and a Bravo executive. Four Teamsters were indicted but acquitted. O’Brien was never indicted in the controversy, but his No. 2, Mark Harrington, pled guilty to attempted extortion and was sentenced to six months of home confinement. But O’Brien has had his own brushes with discipline over union activities. After he said in 2013 that members who didn’t vote in a Rhode Island Teamsters election the way he wanted would be “punished,” an independent oversight board for the union suspended him on intimidation grounds.

The time O’Brien spent around sets appears to have honed his showman instincts. He flies in to Southern California periodically to record celebrity episodes of his podcast in person at a studio in Burbank. On the show, O’Brien deploys his Boston brogue to offer a mix of wisecracks and humblebrags. One running theme is guests noting how tough he is, a fact O’Brien tends to laugh at while also pointedly not dissenting. Taking a page from early Joe Rogan, O’Brien brings on figures from across the political spectrum, everyone from Hasan Piker and Ro Khanna to Hawley and Chavez-DeRemer, along with subjects like Casey Affleck and Dana White.

Even as he now jets around the country, O’Brien’s Boston working-class roots are visible. He is said to have several plainclothes security guards. One is believed to be Daniel Risteen, a longtime Massachusetts state trooper who had a small role in The Departed. Risteen left the troopers in 2018 amid one controversy over an altered arrest report for a judge’s daughter and another reportedly regarding Risteen’s ex-girlfriend, a trooper who’d admitted to money laundering and drug dealing. Per the union’s latest financial disclosure form, he made a $241,000 salary in 2024.

O’Brien in fact nearly became a TV player years earlier, when friend Mark Wahlberg and the actor’s manager Stephen Levinson pitched a Teamsters-themed unscripted show to A&E that would focus on Local 25. The pilot was shot in 2012, but the show was never picked up.

O’Brien by his own admission spends more time on the road and less in D.C. than past Teamsters bosses, and while it no doubt has contributed to his profile, it also has made some critics grumble that he has larger media or political ambitions.

For now, though, O’Brien appears to have his eye trained on a different vote: his Teamsters reelection bid in fall 2026. In April, O’Brien announced his slate, showing he again will be running alongside his current secretary-treasurer Fred Zuckerman and a list of candidates including Dougherty.

The landscape of potential O’Brien challengers isn’t yet clear, but Hooker, the Philadelphia Local official, is one of them. The Teamster leader says he wants to end a culture of “fear, intimidation, retaliation, autocracy and harassment in our organization” that he believes O’Brien, whom he calls a “bully ruler,” perpetuates. O’Brien may also have to answer for his associations with Trump, whose popularity among members could fluctuate over the next 15 months.

Whatever happens in his campaign, O’Brien thinks history will bear out his move from the Democrats and prove the naysayers wrong.

“It was like the definition of insanity, right? Let’s keep supporting the people that aren’t supporting us and get no return on our investment,” he says, referring to unnamed Democratic politicians. “A lot of Democrats, a lot of Democratic representatives, have shifted to big business, to corporations like Amazon, like the Apples of the world and the Ubers, the Lyfts. But we don’t go along to get along. That’s not the type of people we are.”

Rebecca Keegan contributed to this report.

This story appeared in the July 9 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Leave a Reply