Google has agreed to purchase electricity from a forthcoming nuclear fusion power plant, the so-called holy grail of clean energy that scientists have been chasing for more than half a century.

While the fusion industry reached a significant milestone a few years ago, the technology has yet to prove whether it can be a technically feasible or commercially viable option. Nevertheless, the deal Google announced today shows confidence in the possibility of harnessing nuclear fusion to power its data centers.

The news follows the release of Google’s latest sustainability report on Friday, which shows its greenhouse gas emissions continuing to climb despite its clean energy commitments. Even in a best-case scenario, fusion reactors wouldn’t be online in time to help Google meet its goal of slashing emissions by 2030.

“It’s a world-changing technology in our view.”

“It’s a world-changing technology in our view,” Michael Terrell, head of advanced energy at Google, said in a Friday call with reporters. “Yes, there are some serious physics and engineering challenges that we still have to work through to make it commercially viable and scalable. But that’s something that we want to be investing in now to realize that future.”

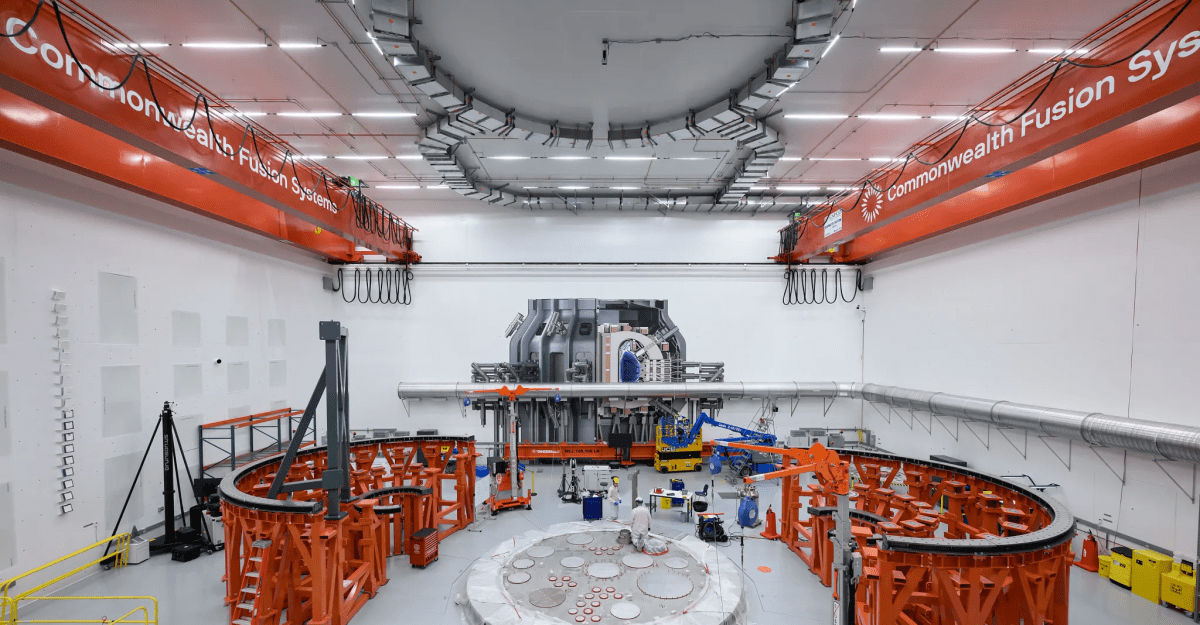

Specifically, Google has agreed to purchase 200 megawatts of “future carbon-free power” from Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS), a private company that is building the fusion plant in question and in which Google is also an investor. Offtake agreements like this are common for other sources of electricity as a way to fund new projects. What’s different here is that the timeline for nuclear fusion is far more uncertain.

Nuclear fusion researchers are attempting to recreate the way stars generate their own light and heat. In our sun, hydrogen nuclei fuse together, creating helium and a tremendous amount of energy. If someone can figure out how to do that in a controlled way on Earth, they would unlock a potentially limitless source of carbon pollution-free energy.

But doing so takes extreme heat — more than 100 million degrees Celsius. With such high temperature and pressure requirements, scientists weren’t even able to achieve a net energy gain from a fusion reaction until 2022. And so far, only the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory has been able to do this. (Today’s nuclear power plants generate electricity through fission — releasing energy by splitting atoms apart rather than fusing them together; a process that leaves behind radioactive waste.)

CFS says the technology is finally advancing fast enough to connect its first fusion power plant to the electricity grid in Virginia by the early 2030s. Virginia is also home to “data center alley,” where tech companies have built or expanded facilities to develop new AI tools. Other energy experts The Verge has spoken to over the years, however, think it could take decades longer for fusion to become commercially available. CFS is currently building its pilot plant in Massachusetts.

Google and CFS aren’t alone in their ambitions. Microsoft inked a deal in 2023 to purchase electricity from a nuclear fusion generator being developed by Helion Energy, which is supposed to be ready by 2028. Around $8 billion from primarily private investors has flowed into fusion startups in recent years, the Washington Post reported last week.

Google first announced an initial investment in CFS to support R&D back in 2021. It’s now making a second capital investment, although the companies aren’t disclosing any concrete numbers. Google has also been an investor in another fusion company, TAE Technologies, since 2015 — although the recent deal with CFS marks Google’s first offtake agreement for fusion.

In 2021, Google pledged to reduce its planet-heating pollution by 50 percent by the end of the decade compared to a 2019 baseline. The company’s latest sustainability report, however, shows that the its carbon emissions have actually ballooned by more than 50 percent since 2019 as it doubles down on AI.

The 200MW deal with CFS represents a fraction of Google’s carbon-free energy purchases. It says it has signed more than 170 agreements since 2010 to purchase 22,000MW of clean energy — much of that in wind and solar projects that it sees as more feasible near-term solutions.

Leave a Reply