Sony Pictures

Sony PicturesWhen 28 Days Later hit screens in 2002, it unleashed a new tangible sense of everyday terror, as Cillian Murphy stumbled around London’s chillingly deserted streets and landmarks, emptied by a zombie virus outbreak.

In March 2020, the dystopian nightmare became reality when the Covid pandemic transformed the capital into a ghost town. Whereas Murphy’s character saw Oxford Street awash with “missing” posters, today a memorial wall stands opposite Parliament to commemorate the 200,000 UK dead.

It is in this ever-changed climate that original director Danny Boyle and writer Alex Garland have returned to their virus-filled world with 28 Years Later.

Speaking to BBC News, Boyle says that for audiences, going through a sudden life-threatening transformation – even without zombies – has intensified the terror, because “what we used to think only belonged in movies” now “feels more possible”.

But it is the way we adapted to Covid, and learned to live within the confines of an unstable, vulnerable reality, that he says is central to the new film.

Life after survival

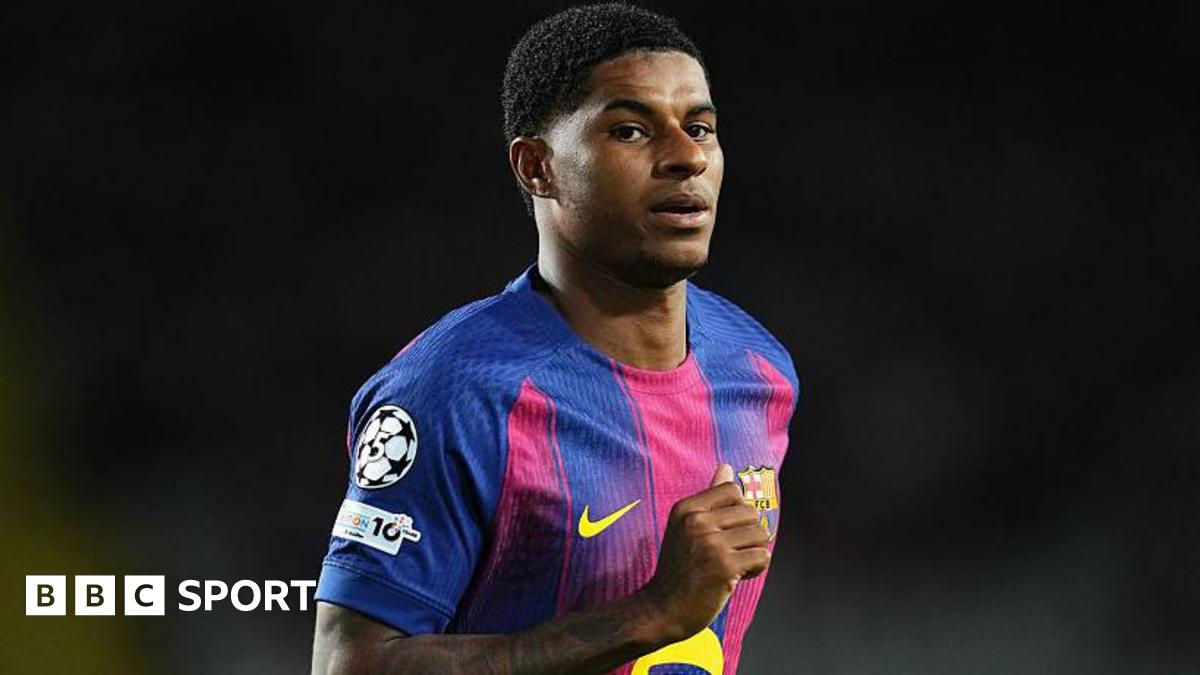

In this latest chapter, the “infected” – victims of the lab-leaked Rage Virus, last shown reaching Europe at the end of Juan Carlos Fresnadillo’s 2007 sequel 28 Weeks Later – have been pushed back and re-confined to British shores.

As the rest of the world heals, Britain’s remaining survivors have been left to fend for themselves.

Among them is 12-year-old Spike (Alfie Williams), who lives with his father Jamie (Aaron Taylor-Johnson) and housebound mother Isla (Jodie Comer) on Holy Island, off England’s north-east coast. He’s only ever known a feudal life in this 150-strong sanctuary, connected to the quarantined mainland by a single, heavily defended causeway that’s only accessible at low tide.

Alamy

AlamyNow the gap between adults and children isn’t just generational – it’s divided between those who remember life pre-outbreak and those born post-virus. The needs-must attitude sees Jamie take Spike on a rite of passage hunt on the mainland for his 12th birthday.

Just as humanity appears to have adapted, so too have the infected – who are now more evolved. Some crawl, while others have become Alphas, leading fast-running packs. The Rage Virus, it seems, never quietened – it grew.

“Gradually, you start to take more risks – you start to explore just how far you can go and still stay safe,” Boyle says of the film’s Covid parallels. “That’s unimaginable 28 days after the infection. But 28 years after the infection, those are the kinds of risks they take.”

Hard truths

Boyle says the decision to have a young lead character was intentional, not only because “horror loves innocence”, but also to explore the truths adults choose to tell children – and hide from them – in order to keep going.

The emotional tension is something Comer can relate to, on and off screen.

“I’ve felt it with my own parents,” she says, speaking to me beside Boyle. “When they’ve tried to protect me from something, thinking it was better not to worry me. But there have been moments where I’ve thought, I really wish you’d shared that with me because I might have done something differently… or had more time with someone. But ultimately, it’s always coming from a place of love.”

Sony Pictures

Sony PicturesIt’s a trait shared by her character, Isla. As mother to Spike, Isla is clearly sick but still desperately trying to care for him, even while slipping in and out of lucidity – apparently ravaged with confusion from decades under siege. But the reality is more complex.

Zombie nation

Comer is no stranger to crisis storylines. She played the mother of a newborn facing an apocalyptic flood in The End We Start From, and a care home nurse in Covid drama Help! But 28 Years Later marks her first portrayal of someone so deep into post-apocalyptic living.

It’s also her first time facing zombies. So what’s it like being chased by the infected? “Thrilling,” she replies.

The scenes were grounded in the film’s gritty realism. No CGI or green screen was used, with the “infected” actors sometimes spending hours in the make-up chair.

“These performers, they aren’t taking the pace off,” she says with a laugh. “There are moments that feel incredibly heightened – you’re out of breath, facing elements of hysteria – but it’s brilliant.”

Isla goes from debilitation to windows of composure: helping to deliver a baby or seeing off one of the infected with muscle memory precision that shows a glimpse of her past.

Comer admits that navigating the emotional “ebbs and flows” of Isla’s awareness was the most difficult aspect of the role.

Sony Pictures

Sony PicturesBoyle’s films – from Trainspotting to the Oscar-winning Slumdog Millionaire – have always explored social truths. For him, the subtlety of Isla’s relationship with Spike is important, as she helps the boy understand there’s more to life than what the director calls “aggressive manhood”.

“There are different ways of progressing,” Boyle says. “And he learns that, I think. He’s able to step out into the world more fully armed than what just bows and arrows gives him.”

Comer adds: “There’s an essence of hope through him and his curiosity.”

Boyle sees this film as the first of a trilogy, with Spike potentially appearing in all three.

The second film, already shot by director Nia DaCosta, with Garland again writing, is due for release next year. Boyle plans to return for the third film, if it’s green-lit.

Real-world rage virus

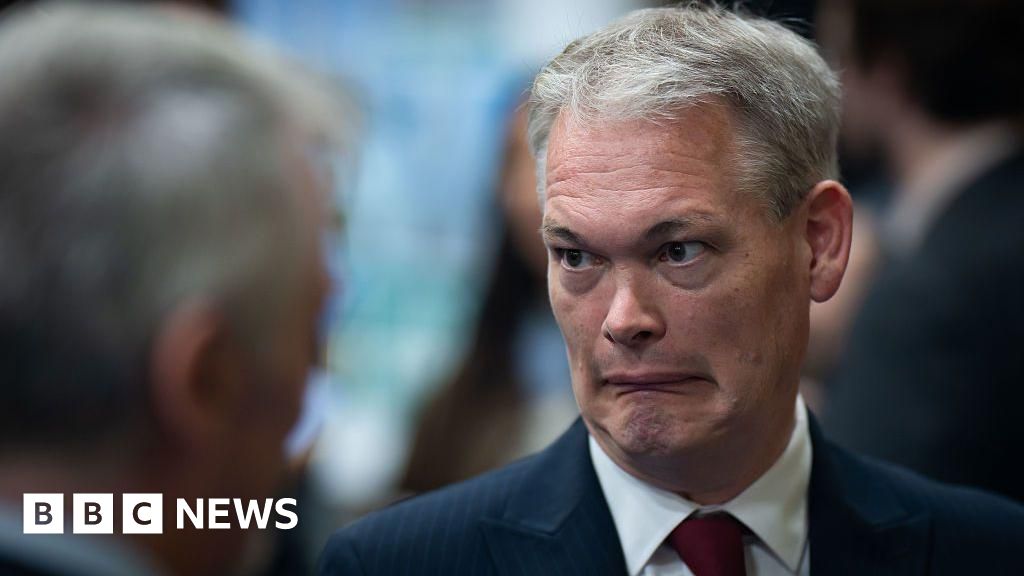

When I ask Boyle why, as a director of many genres, he’s returning to horror so ambitiously, especially with the zombie-ridden The Last of Us TV adaptation dominating the zeitgeist, he suggests he was spurred on by an urgent political undercurrent.

Alongside Spike’s lessons in humanity, Boyle highlights a stagnant culture on the island, which is “not progressive, standing still… looking back to the halcyon days of England”.

The director describes the island’s feudal way of life as deceptively safe but ultimately regressive – something Spike comes to realise.

For Boyle, it reflects today’s political climate and its dangers. “I think putting that in a horror film is a good thing,” he says. “Because I think it will lead us to horror – and we know it will. We can see it beginning to happen even around us. Horror is a great genre for that, and it’s one of the reasons it remains so popular.”

With so much real conflict around the globe, horror films feed off the sense that “huge change could be just around the corner” in the world as we know it, Boyle says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn the original 28 Days Later, the Rage Virus was developed by forcing chimps to watch graphic video footage.

I ask Boyle whether he sees a parallel in the real-life rise of social media, with its personalised algorithm that’s designed to reward polarising, rage-inducing content.

“We’re encouraged to communicate through these things,” he replies, swiftly holding up his phone. “They’re incredibly powerful – and easily manipulable. But they make us go through [the screen] to talk to each other.”

By contrast, he says there’s “something intangible but amazing about cinema” and other collective human experiences.

What matters is the authentic connection from cinema – sharing something “which is not about this”, he says, gesturing to his phone.

“It’s very fragile, but it’s very important, and we must hang on to it, as much as can.”

For Boyle, then, 28 Years Later is about audiences facing terror as one as much as the horror itself – real or imagined. Two decades on, we know all too well how they can blur.

Leave a Reply