It was clear from the start of his career with the Nashville majors that Parker McCollum was not just another one of the boys coming up through the Music Row machinery. He had the goods to become a true breakout star, and McCollum’s first four singles in a row through MCA Nashville all went to No. 1 on either the Billboard or Mediabase country airplay charts, along with going platinum (or triple-platinum, in the case of 2020’s “Pretty Heart”). But even in an age of increasing country homogenization, artists from Texas are inevitably just a little different from artists from any other part of the country, and McCollum is the ultimate proof of how that still holds true, or should. His heroes are some of the longstanding heroes of Texas-brewed Americana music — albeit with a healthy does of George Strait adoration to bring him closer to the center.

“I’ve never sat down one time and thought, ‘Man, I’m gonna try to write a hit’ or ‘I’m gonna try to write a song that could be on the radio,’ ever,” says McCollum, who is making a pretty bold claim, when it’s hard to find a singer on a major Nashville label who won’t admit to at least a slight mercenary streak. “I’m just lucky that some of the ones I’ve written have been able to find success at radio. It’s certainly helped and it’s not a bad thing at all, but it’s never my intention.” Specifically, you won’t hear him adopting any of the most familiar modern tropes: “I was never gonna go write pickup truck and beer songs.”

The 33-year-old Austin native has a new album out this weekend, titled simply “Parker McCollum,” an eponymous reflection of just how sure he is that he got to the heart of his art with his third album for MCA (and fifth overall, including two mid-2010s independent releases). It’s the first time he’s worked with producer Frank Liddell, famous in part for setting up Miranda Lambert‘s early success. (Liddell’s wife, Lee Ann Womack, makes a vocal cameo on the album, as does daughter Aubrie Sellers, who has joined McCollum’s touring band as a backing vocalist.)

On a visit to Los Angeles earlier this week, McCollum sat down with Variety to discuss this impressive new album, where he picked up his love of artists like Chris Knight, Rodney Crowell and Guy Clark, and how he’s fine if going just a bit left of center with the self-titled effort does or doesn’t keep him topping the charts.=

You’re an artist who came out of the gate with a lot of credibility, so it’s not as if there was some big leap you needed to take, necessarily. But it sounds like, with this album, you did have it in mind at some point to do something that you felt was closer to what some of your heroes would be doing. Is that right?

Yeah, I just think I was trying to really honestly see what I was made of. I felt like I’d gotten super comfortable with the creative process. It kind of felt like it was pretty turnkey, and I knew the drill and how it was gonna go. I really wanted to go get really uncomfortable. And I had some songs I had written that I really thought a lot of, which is rare for me, since I never think anything I do is good. … And you know, all I ever wanted to do is be a country singer, but then the longer I do it and the more records I put out, I’m like, maybe it doesn’t really sound like country music to me when I sing, or the songs that I write. And that’s totally fine. I don’t know what I sound like, what I am or what it is I’m supposed to be, but I’m just gonna quit worrying about it —and whatever it is that I do sound like, just do that, and its most raw and genuine and authentic form.

You had a new creative team this time, with Frank Liddell as your partner, after working with Jon Randall on your previous albums for Universal.

Frank Liddell, who produced the record, and Eric Masse, who engineered it, were really down to go down that rabbit hole and get as weird or as wild as I wanted to get and chase whatever I wanted to chase. And Frank was really the first producer that ever was like, “Hey, you’re really good, and you need to go in there and fucking act like it.” That really resonated with me, because that’s not my style at all. During the one week we were in New York recording this record, he just kept telling me, “Hey, you’re really good. Act like it.” And so I would walk in the studio every morning in New York and I’d be like, “I’m really good! I’m gonna act like it.” And as soon as I left, I was back to fully believing that I was not. But for that week, it worked. And that was really interesting, to let my guard down a little bit, and just be like, “Man, whatever it is that I do, that’s what I’m gonna do.”

Looking back on your first two major-label albums, are you proud of those, or do you feel like you were missing the mark somehow?

No, I loved those records. I always wanted to hear myself sonically perfect. Like when I listen to a George Strait record or a John Mayer record and they just sound unbelievably perfect, I always wanted to hear myself that way. I wanted to sign a major deal and cut records in big studios on big budgets and sound so sonically clean. And it wasn’t really that I was trying to get away from that on this record. But between me and Frank and Eric discussing how we wanted to make this record, they just were really adamant about me just being me. Whatever it is that I was or whatever it is that I am, just go be that and do it and own it. And don’t try to be a “country singer”; just try to be Parker McCollum. And then Parker McCollum, the real me, is not sonically perfect.

You started making another album with Jon Randall producing, and then abandoned that midway to start over with this new approach with Liddell, didn’t you?

Yeah, we cut pretty much half a record. And it just felt the same as the last one, and what me and Jon Randall were cooking up was still sounding great. I just didn’t feel like I was improving or going to the next level or challenging myself. I was very comfortable, and I don’t think that’s always conducive to making great art and writing songs that move people. My favorite songs are the ones that really make me perk up when something just hits me in my bones and in my gut. And so I felt like the only way to achieve that was to just strip everything away and start completely over and go somewhere like New York City and just focus. And, really, Frank got such a better version of me than Jon got. I was much more focused, much more aware. I didn’t know what I wanted to do at that point, but I knew what I didn’t want to do. With Frank, there was nothing we weren’t willing to try and no place we weren’t willing to go, and I think you can hear that on the record.

Were you a fan of any of Liddell’s records in particular, to cold-call him like you did?

He produced a Chris Knight record. That was the first Chris Knight record I ever heard, and there was a song off that record called “Framed” that was the first song I ever learned to sing and play on guitar when I was in seventh grade. And I knew if Frank Liddell could hear Chris Knight and want to produce his records and understand what Chris was, he could hear these songs and hopefully at least understand it to the same level. And he really made me believe in myself again.

People might find it hard to believe you’ve had a hard time believing in yourself, when you had a string of No. 1 records, which is very validating, obviously, and you liked them; it’s not like you were making something you didn’t stand behind. So where did the disbelief come in?

Nothing makes you believe more that you’re not good than going into the studio — anytime, anywhere — and having to listen back to it. You know, I’ve never thought I was a good singer, never thought I was a good songwriter, never thought I was a good guitar player. And Frank just disagreed with all of that. He was just like, “You’re a really good songwriter, you’re a really good singer, you’re a really good guitar player.” And that was enough for me to be like, OK, maybe I am. And he was so down to go find whatever the hell it was that I was looking for, and that’s hard to find. It’s hard to find a producer that’s working on a major label record on a massive budget and doesn’t give a shit what anybody thinks. And Frank is not worried about pleasing anybody. He’s just worried about giving the most to every song as you possibly can, and when we were in New York, it really allowed me to feel the same way.

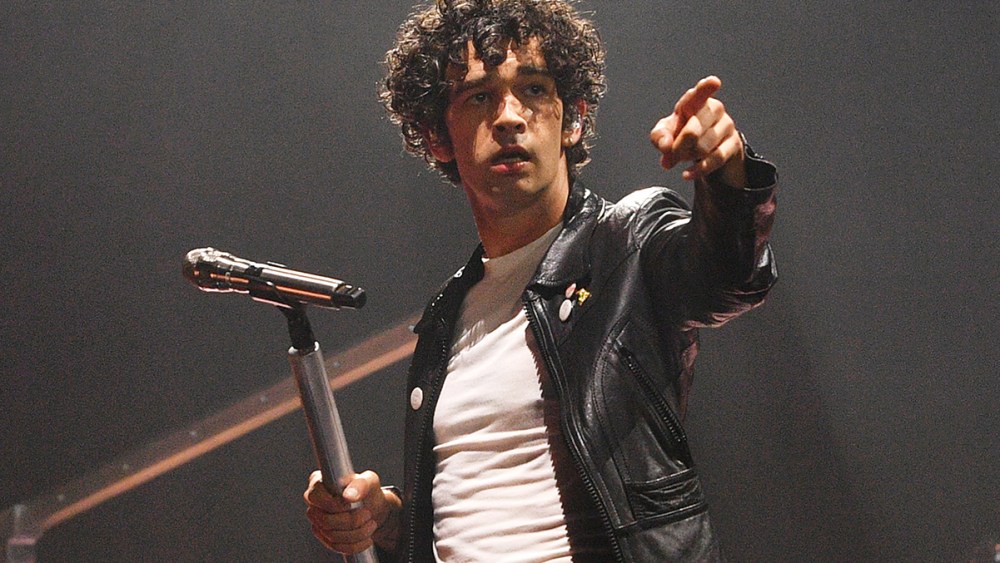

Parker McCollum poses for a portrat at MCM Hollywood Hills Recording Studio on June 23, 2025 in Studio City, California.

Michael Buckner for Variety

Are the songs on this version of the album the same ones you had been starting to cut with Jon Randall?

I think there were just a couple songs that I’d cut with JR that made it to this record…

So were the rest of the songs material that you had in the bag, but had just not even considered for the first attempt at doing the album?

Correct. Plus there was one song we wrote called “New York Is On Fire” that we wrote on the second day in the studio, at 9 o’clock in the morning. And I absolutely hated it; I thought it was the worst thing I’d ever done. And then by the end of the week, I was like, “Holy shit, it’s one of the best songs on the record.” And that was all Frank. He was like, “Just keep playing it, keep playing it, keep playing it.” It was mind-numbing how many times we cut that song, but then when we listened back to it on the seventh day, it just was magical. And then the oldest song on the record is one I wrote when I was 15, called “Permanent Headphones.” So my oldest song and my newest song are back-to-back on the record, which is kind of cool.

What are the songs in this record that you are most proud of?

I don’t think there’s one that doesn’t mean a lot to me. None of the songs sound the same. I think top to bottom, it’s almost cinematic, the feel of the record, if you listen to it all the way through. When the record was done and we sent it to the record label, I made sure it was a continuous recording, so they couldn’t just pick a track and listen to it; they had to listen to the entire thing, because that’s really how it was kind of designed and put together. I thought it all had its own identity and every song was its own thing, and I feel like you don’t hear that a ton in country music nowadays. I feel like a lot of people have a hit and they kind of continue to try to recreate that, and I’ve never done that. … But I think this record’s probably as good as it’s ever gonna get from me.

There are big changes afoot at your label, MCA, formerly UMG Nashville. Did that concern you?

I don’t really worry about that stuff much. They’re gonna do whatever they do and I’ve gotta do whatever I’m gonna do. But several people who have been there for 20 years have said, “This is the greatest record that this label has seen since I’ve been here.” And every one of them that said that knows me well enough that they don’t bullshit me or else I would call ’em out. I would know if they were blowing smoke, and I believed them. And that was surprising to me, because the whole time I was in New York, I was like, “Dude, the record label, they’re gonna shit. They’re gonna be so pissed when they hear this thing.” And it couldn’t have been more opposite. It was like a breath of fresh air, I think, for them to have a record that felt so complete and so honest, and so raw and so unique and didn’t sound like anything else.

I think it’s me in the most honest, vulnerable place I could possibly go to. And when I was thinking, “They’re gonna fucking be pissed. They’re gonna go, ‘We wasted half a million dollars,’” it was nice that they just got so on board. I mean, one of the top people at MCA texted me this morning and was like, “Yo, this is the best record I’ve ever worked on this label.” Which probably means it’ll shit the bed. But I don’t care. I just think it’s the record I always wondered if I was good enough to make, so I can live with it and hang my hat on it, regardless of numbers or performance.

Do you think everyone involved on the business side for you got you right away, and knew and accepted you had this independent streak?

I mean, when I signed my deal, I told them very plain and clear, “Look, I will only sign this deal if y’all promise me that I cut what I want to cut, I write what I wanna write, and I record what I wanna record, end of story.” They agreed to that, and they have held their word on that 100 and have never told me anything creatively at any point in time. So, you know, having the first four singles be No. 1 and platinum and all that stuff certainly allows them to keep their word on that a little easier. I’m sure if it wasn’t going as well, it’d be a different story. … But I’m the one that’s gotta get up there and sing ’em every night and live with it. They can go sign another artist and promote them if it doesn’t work for me. So it’s nice that they’ve had my back.

Was there anything specifically about recording in New York instead of Nashville that you think affected the record?

It allowed everybody to focus. Nobody had to go leave and pick up their kids at 5 o’clock. The label wasn’t stopping by. We had no distractions. I didn’t go to a bar or a restaurant the whole time I was there. I went from the hotel room to the studio and back every single day. It was all intentional: I wanted to go there in the late fall and the trees were changing colors, which is how I got the “New York Is on Fire” idea when I was flying in and saw Central Park being electric orange. Everybody was able to go there and really feel like they were a part of something that was bigger than all of us, and the level of focus, I think, was heightened quite a bit by the fact that we weren’t in Nashville and having to go run errands. That was really helpful to allow everybody to just buy in.

It’s hard to feel like a rock star when you gotta pick your kids up at 5 o’clock, you know? You go to New York and I feel like I’m somebody in that city — which is crazy, because you can be the most famous person in the world and walk down the street and nobody gives a shit or even looks twice! But for some reason, still, when I’m in that city, it just gives me a little pep in my step, a little buzz.

So you recommend that to people in country who are used to cutting the standard way in Nashville?

I mean, my first two (independent) albums, that’s how I cut ’em — I cut ’em both in a week, just five, six, seven days of going to the studio every day and just hammering it out, really being focused. But then when I signed my deal, I was touring so much and it was going so well and we were so busy. So I would swing into the studio on a Tuesday and cut a few songs, and then a couple months later, I’d cut a few more songs, and at the end of the year I’d be like, “Right, we gotta put a record out. So what have we recorded?” And nothing really felt like it had an entire identity. So… I don’t think I’ll ever go away from cutting records like this. This’ll be the only way I do it for the rest of however long I do this.

You have a song on this album where you mention Guy Clark, John Prine and Rodney Crowell. Which is a little different from everyone else invoking Johnny and June, or the usual suspects.

I really don’t like name-dropping artists in songs, either. I’ve always been pretty against it and I’ve just always tried to avoid it. But it seemed like when we were writing that song, “Solid Country Gold,” it was just totally fine that one time. When we were writing it, I was like, “Yeah, it sure seems like it wants that, doesn’t it?” That song is just talking about how things used to be and the days that you miss and those memories in your mind that literally glow when you think about ’em. And those guys’ records are what I was listening to back then, and when I look back and think about those days, those are the songs that take me back to those times. So I was like, “OK, I’m fine to name-drop these guys, this one time.”

Parker McCollum poses for a portrat at MCM Hollywood Hills Recording Studio on June 23, 2025 in Studio City, California.

Michael Buckner for Variety

I’m curious about how you get some of your influences, because I know you’re a ‘90s kid, so it’s surprising an artist has young as you has those artists as touchstones.

Yeah. It is my older brother, who’s six years older than me. When he was in high school, he was really into Rodney Crowell, and in his college years he really got into Townes Van Zandt, Steve Earle, James McMurtry — I mean, the list goes on and on and on. I was just the younger brother who was just so enamored with anything that he thought was cool and thought was good. There was nobody else my age when I was in seventh and eighth grade who knew who Guy Clark or John Prine or Steve Earle was. They had never heard of ‘em, and I was just obsessed. That’s also Todd Snider and Hayes Carll and Chris Knight and Robert Earl Keen, and you name it. I wanted to be those guys when I was a kid because my brother did. He was in love with really, really raw Americana songwriters. And I just identified with it and was just so unbelievably obsessed at such a young age. Those are the guys I would listen to and hope to one day write songs like, and I’m still still trying to write songs like those guys. But it all comes from him.

Even being six years older than you, that still seems young to love that stuff.

You know, I don’t know how the hell he discovered who they were, but he was very, very convicted on what good songs were and who good songwriters were. And if he said they were cool, they were cool.

So did you get to this point without ever having a big conflict in your mind, like, “I need to be a No. 1 country star, so I’m gonna have to leave some of these influences behind and play a different kind of game a little bit”?

No. I mean, I was never gonna go write pickup truck and beer songs. Those songs have never moved me or done anything for me. I don’t think I could get up on stage and sing them, and I was never gonna write ’em. And one thing that my older brother really hammered into my head as I was young was, “You’ve gotta live the songs that you write.” And I probably took that way too seriously for a long time in my early twenties. But, yeah, even when I signed a major record deal, I was like: I’m still gonna go try to write great songs and write songs that I really believe in.

And so the only thing that ever changed was the (glossier) production. Which I wanted! I wanted to hear what I sounded like with that kind of production. And it worked and it was great. But then, it was kind of like: What’s next? What do I do now? And that’s how I got to this record.

“What Kind of Man” was the first single off this album. There is a quote in the promotional material where you say that this song describes someone you were on your way to being when you were a little younger. Can you explain what you meant by that?

Well, I have no idea. I was probably just talking shit. You know, I’ve never sat down ever, one time, to write a song about any specific thing or person. A lot of times I’ll get into a melody, and then there’s certainly things or people or places I’ve been or things I’ve done that kind of find their way into the melody and into the song. But with “What Kind of Man,” I was just sitting around bullshitting and I just sang the line, “Look at that. I done stayed up all night again,” which I used to do all of the time. And I remember I wrote that first verse and that chorus just sitting in the house by myself, and I never really thought that that song would be a single or anything.

I jknew the label wanted to put another song to radio, and that song and “Hope That I’m Enough” were the only two songs we’d recorded at the time. I was really pushing for “Hope That I’m Enough” to be the single, just because I thought it was such a great song. But for radio’s sake and testing and tempo and all that shit, “What Kind of Man” was kind of the easy answer for them. But you know, I’ve never sat down one time and thought, “Man, I’m gonna try to write a hit” or “I’m gonna try to write a song that could be on the radio,” ever. It’s never crossed my mind while writing a song. I’m just lucky that some of the ones I’ve written have been able to find success at radio. It’s certainly helped and it’s not a bad thing at all, but it’s never my intention.

So you never start with the lyrics?

The melody presents the concept. The melody kind of writes the song… It’s like with “Killin’ Me” on this album — once I started singing that melody, that song felt slow and sexy, and there was no question what that song was supposed to be about. I don’t think that melody would serve any other concept other than: up against the bedroom wall, getting naked, naughty.

All of the melodies that I’ve ever come up with just kind of arrive to their destination on their own. You know, I never really think too much about: What is this song about? I never want a map. I don’t want to lead them point A to point B. It doesn’t really have to make sense. And in Nashville, a lot of the songwriters really want to map it out. They want it to be very simple, and it’s gotta make sense. But, like, it just really doesn’t have to. Not to say that it can’t and that it won’t, but it’s OK if it doesn’t. You know, let them figure out what they want it to be about.

Parker McCollum poses for a portrat at MCM Hollywood Hills Recording Studio on June 23, 2025 in Studio City, California.

Michael Buckner for Variety

You do have some writing collaborators who we find as part of Music Row writers’ rooms. Do you feel like you do well in the typical writers’ room sort situation?

No. Anytime I have a co-write… “Hoping I’m Enough” and “What Kind of Man” were both about getting together to write where I was like, “Hey, I’ve got a verse and the chorus. Let’s write a second verse,” and I’m out. I do not like co-writing. I don’t do it well. But in those, I already had a melody; I already had a verse and the chorus — I just needed to finish the song. And it’s an easy way for me to get out of that co-write very quickly.

You came up in conversation with Miranda Lambert recently, and she was singing your praises. You did something with her on her most recent album.

Yeah, on her last record “Postcards from Texas,” called “Santa Fe.” I just think she’s one of the greatest to ever do it. And she called me crying a couple weeks ago. I’d sent her the record and she listened to it and she’s like, “Holy fucking shit.” So to get a phone call like that from someone that you respect their work and you value their opinion so much, somebody who knows good records, knows good songwriting, that was cool to get that phone call.

We’ve talked about the Chris Knight/Rodney Crowell/Guy Clark side of you. But you also talk about George Strait. Besides just the Texas connection, where does the George Strait side of you come in?

For me, really, it’s that I’d love to be the next George Strait off the stage. You know, the way he’s built his career… unbelievably humble and quiet and under the radar, no scandals, no publicity, no bullshit, long career, great songs. He’s consistent and has carried himself so well for so many decades in a business that sees so many artists come and go, remaining so constant and steady, never worried about what anyone else was doing. He’s just stayed 100% George Strait the whole time off the stage, and I’ve always thought that was just so rare. I don’t know another artist that I can think of that has been that way for that long. So that’s really where I draw the line and try to emulate the most I can from him: He’s just a good old boy who just so happens to be the king of country music.

And you think you’ve you got a good bead on that?

Working on it. Long way to go.

Parker McCollum poses for a portrat at MCM Hollywood Hills Recording Studio on June 23, 2025 in Studio City, California.

Michael Buckner

Leave a Reply