One by one, the studios that built Hollywood are falling — or else being folded into one another in such a way that their identities are lost in the process.

First, we saw Amazon swallow MGM, as the studio that once boasted “more stars than there are in heaven” was absorbed by the same company that drove bookstores out of business. Then came the Disney-Fox merger, in which one of the industry’s most prolific studios — the one that gave us everything from “Star Wars” to “The Sound of Music” — was downsized to a spare room of the Mouse House.

Next up appears to be Warner Bros. Discovery, whose shield-shaped logo adorns the water tower looming over its Burbank lot. But not even that can protect the 102-year-old Hollywood institution from being bought out, either by deep-pocketed David Ellison (fresh off his acquisition of Paramount) or an even bigger bidder.

What would be lost if somebody buys Warner Bros.? Depends on who makes the deal, of course, and yet the very possibility demonstrates what a precarious position Hollywood’s most reliable storytellers/sausage-makers now find themselves in. As I write this, I’m sitting on a plane where the screen embedded in the seat before me boasts “the best in streaming content” beneath logos for Disney+, HBO Max and Paramount+. If Ellison were to get his wish, would that mean the latter two streaming services might fold into one: a kind of “HBO ParaMax”? Who would be the Hulu in that equation (the place second-tier Fox movies go to die)?

It wouldn’t be the first time the studio that produced “Casablanca,” “The Searchers” and “2001: A Space Odyssey” had changed hands. Corporate-minded Kinney National Service bought the studio way back in 1969, writing off millions worth of “problematic” projects and assets right away. The company swelled with the Time Warner merger, then landed most of the MGM library (including “Gone With the Wind” to “The Wizard of Oz”) when it gobbled up Turner Broadcasting in 1996.

And there was also the AOL merger in 2001, back before the dot-com crash, when overvalued internet entities had the power to acquire legacy media companies. I worked for AOL in the early aughts, and it was surreal to be working under the same umbrella as the studio whose commitment to the Harry Potter and “Lord of the Rings” series (the latter via its New Line division) revolutionized the franchise business. Here was a company that dedicated never-before-seen resources to story arcs that took as much as a decade to tell. Elsewhere in the company, HBO was showing a similar commitment to “Sex and the City” and “The Sopranos,” revolutionizing what audiences could expect from television.

Nearly a quarter-century later, Warner Bros. is, to this critic’s eyes, the studio willing to take the biggest risks on auteur directors. Who else would have gambled on Ryan Coogler’s Black-and-white-and-red-all-over 1930s vampire epic “Sinners”? Or spent some $130 million for Paul Thomas Anderson to adapt a Thomas Pynchon novel (so loosely it may as well be his original creation)? Or trusted indie darling Greta Gerwig’s vision for “Barbie,” minting gold from a more grown-up approach to the toy brand?

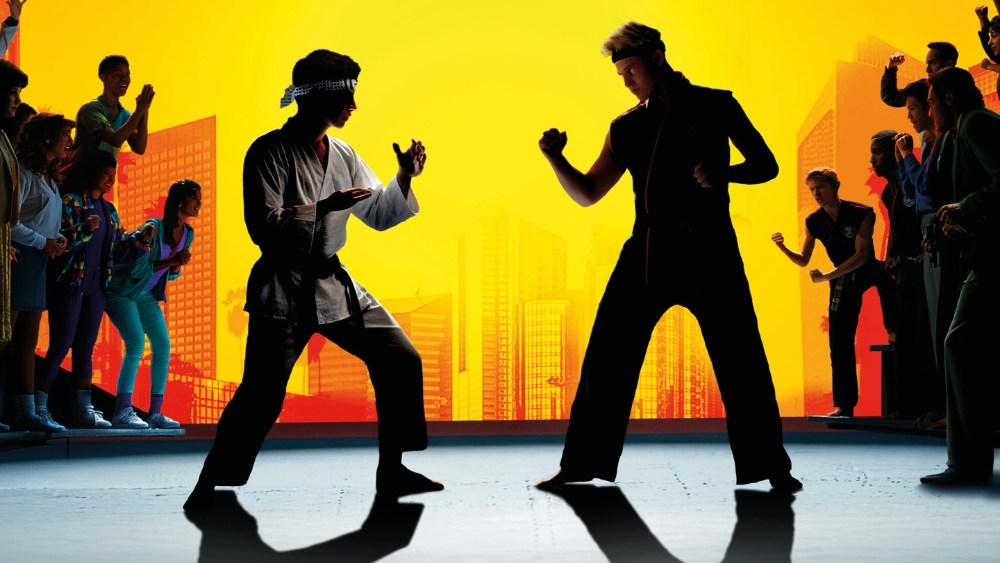

It was Warner that gave Clint Eastwood a place to hang his hat (even if they did wrong by his last film, “Juror No. 2”). The studio offered Christopher Nolan the resources he needed to make massive mind-warps like “Inception” and “Interstellar” between Batman movies (but ultimately lost him to Universal when it came time to make career-best “Oppenheimer”). The studio has taken huge swings on DC heroes, dating all the way back to 1978’s “Superman: The Movie” (but pulled the plug on “Batgirl” because Zaslav saw greater upside in the tax write-off than releasing it). And it has inspired more laughter via its Looney Tunes characters than a million Minions (only to leave the director of “Coyote vs. Acme” in tears after canceling the release of that finished film).

For a while, I worried the studio might send Bong Joon Ho’s oft-delayed “Mickey 17” straight to streaming — a solution that occasionally makes sense, ever since the pandemic disrupted audiences’ moviegoing habits, even as it betrays a fundamental belief in how such films deserve to be seen. (Remember the way Warner did that with “Dune,” rather than waiting the extra year the way Paramount did on “Top Gun: Maverick”?) Warner makes films for the biggest possible screens — but that business model comes at an enormous cost and seems especially vulnerable at a time when no one can predict how audiences will behave.

The studio has had a strong year, what with hits like “Weapons” and “Sinners” helping to cover for the soft performance of “One Battle After Another” and such. If the studio was to win the Oscar, it would be the first time since “Argo” — and yet, Warner movies are nominated nearly every year because the studio cares about quality (more now than in the early days, when it traded largely in musicals and gangster movies). Would that commitment to filmmakers carry forward? That’s why an acquisition makes me nervous, especially so soon after Ellison snapped up Paramount: Each time a studio changes hands, the culture of creativity shifts, and it’s too early to see how he plans to change the studio.

Looking back over just the past half-decade, Warner Bros. is unique in the way it seems to value auteurs above the franchises they launched. Like every studio in town, Warner is in the franchise business, but look how executives allowed the Wachowskis to subvert the execs’ wishes in “The Matrix Resurrections” (which functions as a feature-length critique of cash-grab sequels). Or “Joker: Folie à Deux,” in which the studio allowed Todd Phillips to turn on the original film’s fans. Even “Barbie” pokes fun at the men in the boardroom.

All three films hail from a studio that somehow manages to surprise, and which might see its identity upended entirely in a sale. The Acme in “Coyote vs. Acme” could be read as the in-on-the-joke corporation that made the movie. For years, Warner Discovery seemed too big to fail, when in fact, breaking it down and selling it off might be the only way to keep it alive. The $43 billion question: Will we still recognize it in another form?

Leave a Reply